The Nikon P900 occupies a special place in many topics discussed on Metabunk. It's a fairly lightweight "bridge" camera that has a ridiculously powerful zoom lens. It's described as 83x, or the equivalent of a 2000mm lens on a normal 35mm SLR camera. It replaced the need to carry around several pounds of equipment to get super-zoomed shots. This made it an ideal tool for various communities to use for their interests. Normal ones like bird-spotting or aviation, but also a variety of more conspiracy-oriented topics, including:

- Chemtrails - Where enthusiasts would zoom in on planes leaving contrails and try to pick out anomalies that might suggest some kind of secret spraying program.

- UFOology - Long hampered by regular cameras creating blurry photos of distant blobs, the P900 now gave UFO hunters the opportunity to zoom in on those blobs and see what they actually are. So far those that were resolvable have all turned out to mundane things like birds and balloons, but the UFOlogists are hopeful that one day they will get a zoomed-in (and in-focus) photo of an actual flying craft.

- Flat Earth - No esoteric subject is more synonymous with the P900 than "flat earth". The powerful zoom allows the curious to observe up close a ship vanishing over the curve of the earth, or to see the actual shape of the curve in perspective compressed electrical towers or causeway pylons. Enthusiasts can also recreate classic experiments (like Wallace's Bedford level experiment) that at the time were the domain of the wealthy due to the cost of suitable telescopes - now replaced by a P900.

Chemtrail hunters, UFOlogists, and Flat Earthers are not so concerned with taking pretty pictures. They just want accurate observations. So an increasingly popular modification to the camera (and many other cameras) is to remove a small piece of glass from inside the camera to allow it to detect infrared radiation. This is known as an "IR conversion" or a "full spectrum" conversion.

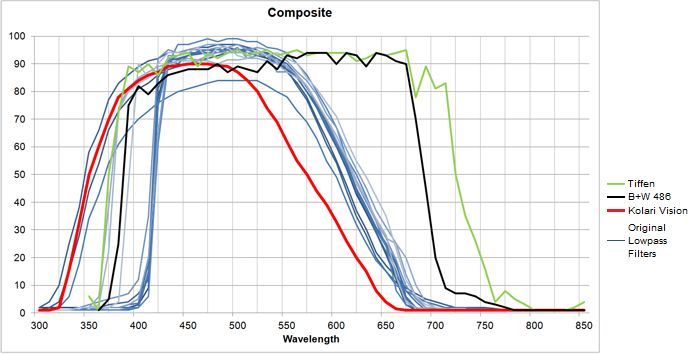

This bit of glass is an infrared (IR) filter. The sensor on the camera is more sensitive than the human eye and can detect light that is not normally visible, particularly infrared light. But including this light in the image give it an unnatural color cast, so most cameras have a filter, this little piece of glass, that removed the IR light, and only allows visible light to hit the sensor, giving a natural appearance, which is great for regular photography.

But this means you are actually removing information from your photo, and when your goal is to get as much information as possible, you really would want the IR light included. So people open up the camera, remove the bit of glass, and they now have a "full spectrum" camera, where all the light that the sensor can detect (visible and IR) is recorded in the photo.

A wonderful benefit of IR light is that it is not scatted as much in the atmosphere. This effectively means IR photography will cut through haze, giving you a much clearer view of objects (or horizons) that are many miles away. To maximize this effect, you add in a filter that blocks all visible light (the light that is scattered). You can replace the bit of glass internally with this filter, but it's more flexible if you get one for the front of the camera. This allows you to take photos in full-spectrum, IR-only (with a $12 filter), or in the original visible light ($100 "hot mirror" filter)

This conversion makes the P9090 a much more suitable tool for all the topics above, particularly Flat Earth, where the effects of haze often obscure long-distance observations. I'm interested in all those subjects, so I had to do it. I put it off for a while, as it's not incredibly easy, and there's some risk of breaking the camera, but as I started seeing more and more example of IR photography being used, I decided to take the plunge.

There are a few tutorials online for how to do this:

- Converting a Nikon p600 camera for IR spotting. (Plasmoid Anomalies Study Group)

- Nikon Coolpix P900 full spectrum / infrared camera modification tutorial (SpaceTech)

- Nikon P900 Infrared Modification - IR Full Detailed (Flat Reality Earth Explorers)

I didn't watch the "Flat reality" video before my conversion, but it does show two ultimately successful conversions, there are a lot of hiccups though, and I'd only watch it if you just want a broader perspective on things that might go wrong. In particular, they keep the camera vertical, when it's easier to have it sat on the lens, with the back horizontal.

I videoed myself doing the operation, but I thought it would be useful to have a step-by-step guide similar to the Plasmoid P600 guide, incorporating what I learned from watching all the videos and performing the operation. So here it is:

STEP BY STEP GUIDE:

Following these instructions will void your warranty, and might damage your camera. The following instructions are informational only, and if you break something, then that is your responsibility. Only attempt if you have the skills and tools required

Step 1 - Gather Your Tools

You will need several things for this operation, get them all before you start:

- Precision Phillips-head screwdriver. Ideally a PH00 size one. If you are unsure, then test it using the two screws in front of the tripod mount. You don't have to remove those screws for the operation, so it's a good place to test. Magnetize the screwdriver, as that makes it MUCH easier to use.

- Small flat head screwdriver (for popping open the case with the tab under the flash, and opening ribbon cable connections)

- Tools for opening the case. Specifically something flat that you can slide in and twist to pop it open. You will probably be fine with fingernails or a small flathead, but I have a $10 set of case opening tools from Prytech, which worked great.

- Tweezers, for reinserting ribbon cables, and picking up screws. Beware of "pinching" eyebrow tweezers as the sharp edge can cut the ribbon cable. Flat angled tweezers are ideal.

- Containers for screws - There's six kinds of screws, so you might want six containers, but either way, you don't want to lose any! You will at the very least want to keep the three sensor screws seperate.

- Pen - which you will use to mark things off this checklist as you through it forwards and then backward.

- Remove the battery (you don't want to accidentally turn it on at a crucial point!)

- Put on a lens cap (as you will be balancing the camera on the lens

- Remove the strap (it gets in the way)

- Fold the screen so it's facing inwards

- Grounding? Some people like to use a grounding strap when working with electronics. I personally do not, but if you frequently get static sparks you might consider it.

- Gloves? Greasy fingers and optics do not go well together. Gloves fix this, but I don't use them as I'm not actually touching any of the glass, and gloves make it harder to handle the small screws.

- Ensure you have an uninterrupted hour

- Familiarize yourself with how ribbon cable connectors work. If you have not done this before you will be tempted to just pull out the ribbon cables. This will break your camera! The connectors have a small tab that goes the full width of the cable that you flip up to remove and press down when you re-insert the cable.

- 1 - Next to the hinge of the battery door on the bottom of the camera

- 2 & 3 - At the back of the tripod mount screw.

- 4 - Next to the USB port under the rubber tab on the right-hand side

- 5 & 6 - On the right hand (grip) side, top, and bottom

- 7 & 8 - On the left-hand side, top and bottom

- 9 & 10 - Under the screen, near the hinge

- 11 & 12 - Under the flash (coarse)

Step 5 - Remove the back of the camera.

- Gently pry the back away from the front, all the way around, but don't try to fully remove it.

- Put the camera on a flat surface, base down. Insert a small flat screwdriver into the slot under the flash (see above) and gently twist. The back should now be pivot open, but is still connected by two ribbon cables on the right side

- Remove the top (short) ribbon cable by flipping up the tab and then removing the cable. It will come out easily once the tab is up.

- (Optional) Remove the second ribbon cable. I did not do this (and neither did SpaceTech) as there seemed to be enough room for maneuvering with this cable still attached. So I ended up with it looking like:

This is probably the most difficult part. Go very slowly here, and never force anything, as some of the cables are quite close of the metal, and can be pinched or stretched. You can do this step with the camera vertical (on its base like above), or face down (resting on the lense). I started with vertical and switched to face down. If you go for face down (which I recommend) and you did not remove the second ribbon cable, then you will need to put the back of the camera on something, like this:

You are going to be removing 11 screws (13-32) and three ribbon cables (3,4 and 5). The screws are all silver and come in three sizes, long, short, and tiny.

- Screw 13, bottom, right of center (long)

- Screw 14, bottom right (long)

- Screw 15, top right (long)

- Screw 16 top, right of center (short)

- Screw 17 top left (short)

- Screw 18 bottom left (short)

- Cable 3, second cable in on the top right.

- Screw 19 (long) is directly under cable 3.

- Screws 20, 21, either side of the viewfinder

- Cable 4, bottom mid. Flip the tab!

- Screw 22, bottom left

- Screw 23, left and down of viewfinder. Tiny screw.

- Cable 5, top center (to viewfinder PCB)

- First, detach the viewfinder PCB from the shield. This is just loosely held in place with some tabs, and should jiggle free easily. Note how it was positioned, with the tab inserted in the metal slot on the upper right

- Then gently pry the shield away from the main circuit board. It is loosely held in place on some small plastic posts. Remember this fact for reassembly, as you will need to pop it back into place.

- Gently position the shield to the left of the camera. It will still be connected with a ribbon cable, but we will be replacing it in a few minutes.

I'm putting these together as you will want do this as quickly as possible to avoid getting dust on the sensor, which is under the copper disk. First, unscrew the three screws, and keep them separate. Then if you gently lift the copper disk (with the sensor attached), you will see:

That little bit of glass is just sat there. With the sensor screwed in place the glass filter is held between a rectangle of black paper with a rectangular cutout, and a similarly shaped piece of black foam in the sensor holder. Both of these might potentially fall out. In my case, only the paper fell out. But in the Flat Reality video, the foam fell too.

Now REMOVE THE FILTER. There are three possible ways of doing this

- Tilt the camera so the filter falls out. This is what I did (because SpaceTech did). The problem here is that the paper falls out too. You can just put it back. Be careful in tilting the camera with the attached ribbon cables.

- Use something sticky - like a bit of tape. Just touch it to the glass and lift it away. Assumes you don't want to use it again.

- Suck it up with a drinking straw.

Note the foam has a corner cut off that would be in the upper left when seated above the paper. If the foam falls off, then I'd put it on top of the paper, rather than attempt to refix it to the sensor container.

Step 9 - Reverse the above steps.

You essentially do everything exactly backward (except for putting the filter back, of course). So screw down the sensor container, then go back up the list of screws and ribbons until everything is back together. Some important points:

- Cables slide into their slots fairly easily. But can be fiddly. Give it some time. Make sure the tab is up, slide it in, and close the tab. Compare with other cables to see if it looks right.

- The copper tab on the sensor container should end up outside the shield. I left it inside with no ill-effects though.

- When reversing step 7, the shield sits on these little posts that are next to the screws. It should pop onto them with light pressure, but you might have to actually screw it down in places so it pops into place. Ensure it DOES pop into place, and is well seated

- Take it SLOW, don't force anything. Be aware of where the ribbon cables are. Make sure they are not pinched.

- Also in Step 7, there's a metal tab near the tripod screw. Ensure this goes INSIDE the case. I had it outside, and had to reverse the reversal a little.

- The bottom ribbon cable has to be tucked back a bit.

- Before putting back all the black screws, you will have to reinsert two pieces of rubber.

- One goes in the bottom right corner, and the other is the cover for the ports. Check that you can snap the back together, and then pry it apart enough to insert these two pieces, then snap back together

- You can run a test now (good idea), or after putting in the rest of the screws (coarse screws under the flash) if you feel lucky (I was lucky).

Step 10 - Switch on.

When you first power on the camera it will take a while, as it has been reset to factory defaults. You will be prompted to enter the date and time. Then take off the lens cap and observe the world in slightly purple full spectrum glory.

If it is not working, then the most likely thing is a ribbon cable that is not inserted well. Go back and look at them and fix any that seem off. If still not working, then go through them one at a time, removing and replacing them. However, the success rate seems fairly high with this operation, unless everyone who failed is too embarrassed to share.

For pure IR, use an IR pass filter. I use a cheap Opteka 67mm R72

Everything will be purple. You can correct this in post, but I like to switch the camera to B&W mode (Shooting Menu/Picture Control/Monochrome). You can adjust the contrast here too - ad added +1 contrast. Doing the B&W conversion in-camera means it's done on the RAW data.

The first plane I saw with my "new" camera was an A380!

Finally, go out and find some UFOs, capture some contrails, and/or observe the Curve

Last edited: