edby

Member

Quite so.There are two locks at Salters Lode, both connecting with the tidal Great Ouse River, but from different non-tidal sources. This has caused confusion to some writers.

http://www.ousewashes.info/sluices/old-bedford-sluice.htm

Quite so.There are two locks at Salters Lode, both connecting with the tidal Great Ouse River, but from different non-tidal sources. This has caused confusion to some writers.

http://www.ousewashes.info/sluices/old-bedford-sluice.htm

"First. The test proposed at p. 5, to place a spirit-level at the middle station, and take a sight both ways to Welney Bridge and Old Bedford Bridge (not Welche's Dam as you state) the water at the two ends would certainly be shown to be about five feet below the horizontal straight line touching the water at the middle station. The only difficulty would be in getting the level placed high enough to be above the vapours and unequally heated air close to the ground; but I have no doubt, if it were placed on the elevated towing path, its height above the water would be about five feet less than the height of the points on the two bridges cut by the cross-hair, which determines the true level line. https://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S179AA.htm

Here is another modern map of the area round Welney. http://www.britishwalks.org/walks/1999/054.php

I have belatedly realised that on Google Earth (at least in the current version with imagery dated 1/1/2007) the land near Welney to the south-east of the Old Bedford River is actually flooded. This tends to obscure the fact that there are two waterways running parallel near Welney: the Old Bedford River and the River Delph. (This is clearer if you zoom in on the map I just linked to.) In consequence, there are currently two bridges at Welney, one over the OBR and one over the Delph. As Rory pointed out, the one over the OBR might well be called the Old Bedford Bridge, but it might equally be called the Welney Bridge to distinguish it from other bridges over the OBR. I do not know if there were two bridges in 1870. [Edit: two bridges are shown in the 1886 OS map shown mentioned earlier in this thread.]

The first step is to clear up this misconception. Perhaps a video showing that this doesn't happen. A video camera on a tripod, demonstrating that there is no parallax shift when the camera is tilted or moved from side to side.

Easy way to tell they weren't using the Delph: the Delph isn't straight.There are indeed two waterways, but Wallace clearly says, in a number of places 'old Bedford river', not Delph river.

That tooEasy way to tell they weren't using the Delph: the Delph isn't straight.

One difficulty, as I mentioned above, is any chain of reasoning involving more than two premises.

What about using scaffolding poles? How long are they?

What about helium balloons, floated on strings 13 feet long? Or would that be too open to accusations of swindling (e.g., the strings could be measured to give the desired results).

I have already had a similar conversation with an FEer at another forum. He claims that refraction in the telescope will cause the position of the markers to change.

FYI a YouTube video using a P900, both directions from Welney Bridge.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2dXoxu_Ua0

Mick, could you explain the 40 PVC tubing bit please?

He has just come back, and evaded the 'different angle' objection. He now claims that even if the observation point is shifted up or downwards, right or left, even by a fraction of an inch, the observation will change. He cites Rowbotham again, and he claims this is because of the 'very great distances' involved.This is a rationalization defending the feeling that tilting causes a parallax shift - and in a larger sense, FE itself. There is nothing in the science of optics that would suggest or support this, and I'm certain that this idea did not come from any knowledge of optics. It was pulled out of a hat.

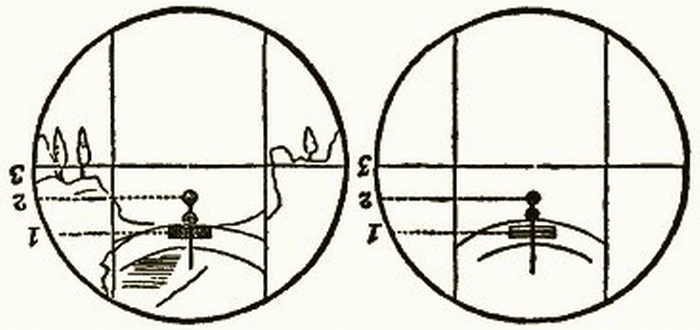

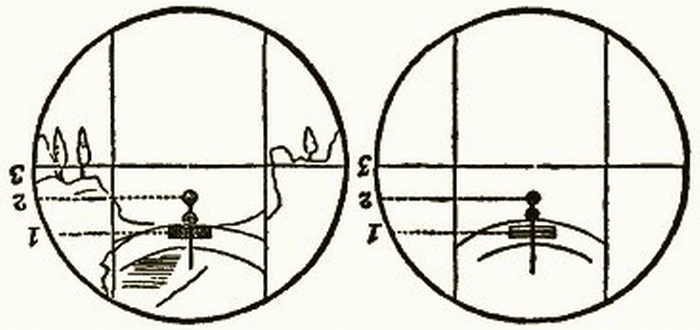

I fixed up a long pole with two red discs on it, the upper one having its centre the same height above the water as the centre of the black band and of the telescope, while the second disc was four feet lower down.

[edit] and some v elementary trig suggests that the viewer would have to be at least 2x4 feet = 8 feet higher in order for the top mark to line up with the black horizontal band. Wallace is brilliant.

I will make some cardboard replicas of the bridge and the midpoint marker to show the 8 foot effect, then make a video.

Here's a video I just made to show how they fit together.Mick, could you explain the 40 PVC tubing bit please?

I am thinking, a tripod structure that goes into the water with weights to hold it down, then a straight bit to give the required height above the water.

He has just come back, and evaded the 'different angle' objection. He now claims that even if the observation point is shifted up or downwards, right or left, even by a fraction of an inch, the observation will change. He cites Rowbotham again, and he claims this is because of the 'very great distances' involved.

"A weighted base would probably work better. The middle of a canal is flat silt, so it should be fairly straight naturally. Here's a standard patio umbrella base with 1" PVC."

I am really liking this. How about the extendibility aspect? The depth of the water is unknown.

Barges are tricky though, for the reasons mentioned. I suggest a thorough 'dry' run.I don't know. I think there was a reason Wallace used a barge. I think if you try this in real life, you'll find that the setup will be unstable. Silt on the bottom of a canal is unstable stuff - the base will sink, tilt... and this will continue to happen and things will change.

A barge will be more stable. And more stable than a boat with a keel, because the flat bottom resists roll.

I don't know. I think there was a reason Wallace used a barge.

External Quote:that the fact that the distant signal appeared below the middle one as far as the middle one did below the cross-hair, proved that the three were in a straight line, and that the earth was flat.

Okay, I've spent the last hour doing some research rather than relying on memory. Just a thumbnail:

Samuel Rowbotham originated the idea that the Wallace experiment (and the entire issue of the dip of the horizon) was flawed due to the optics of telescopes.

William Carpenter had a completely different idea. He had a confused idea about straight lines and that straight lines are level lines. In brief he contended that because the

External Quote:that the fact that the distant signal appeared below the middle one as far as the middle one did below the cross-hair, proved that the three were in a straight line, and that the earth was flat.

William Carpenter had a completely different idea. He had a confused idea about straight lines and that straight lines are level lines. In brief he contended:

External Quote:that the fact that the distant signal appeared below the middle one as far as the middle one did below the cross-hair, proved that the three were in a straight line, and that the earth was flat.

External Quote:Mr Carpenter defines a "straight line" in a manner totally new, as being absolutely identical with a "level line," thus introducing at the outset confusion of terms, and rendering all clear reasoning impossible.

I think, because he wanted to have:External Quote:Mr Carpenter objects to the value of the view in the large telescope, "because it showed but two points, when a comparison had to be instituted between three;" but he omits to state that the telescope itself was placed accurately at the third point, just as was the spirit-level telescope--to the view shown by which he makes no such objection.

External Quote:

He objects that the telescope was not leveled, and goes into a long argument, in which the words "straight line" occur four times, and which, whatever meaning is given to that term, is utterly confused and misleading. He says that I [Wallace] intended to prove that the central signal was five feet above a "straight line" joining the two extreme points. This I both intended to prove and did prove, using the word "straight line" in its proper sense; but Mr Carpenter should not impute to me the absurd mistake he makes himself of thinking that there is, or is supposed to be, a rise above the level at the centre point.

External Quote:

In a letter to Hampden, Wallace noted that if one sighted along a line of poles between Old Bedford Bridge and Welney Bridge, the tops should appear to be "rising higher and higher to the middle point, and thence sinking lower and lower to the furthest one." Carpenter commented as follows:

The surface of the earth is to be seen "rising" and "falling!" How strange! Why, have we not just been provided with the exact amount of curvature in one continuously progressive scale, without any "ups" and "downs," from eight inches in the first mile, to 130 feet in the fourteenth mile? Is Mr. Wallace right, and all the other scientific men wrong? Does the surface of the earth curvate continuously upwards, or continuously downwards, or, first upwards, then downwards? Is there a gradual incline, a gradual decline, or is there first one then the other? These are questions every thoughtful man will ask.

Nonsense! A thoughtful man would easily understand what Wallace meant.

Carpenter and Hampden were unable to deal with any kind of relativity or ambiguity. They maintained that Wallace was trying to prove that there was a "hill of water," and the central target would be five feet above both the telescope and the bridge.External Quote:

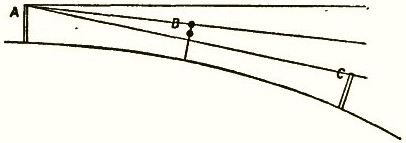

By reference to the annexed diagram it will be seen why these men [Wallace and Walsh] object to state exactly the point on which they take their stand [the literal point on the Earth on which they claim to stand during the survey]. Suppose them to say, as they probably will, they are always on the top [of the Earth], at A; there they have to show a fall of 10 feet 8 inches in the first four miles either way, 16 feet at the end of five miles, 266 feet at the end of forty miles, 1,944 feet at the end of sixty miles, and so on. But, mark—when they get to the end of the four, five, forty, or sixty miles, they will be required to retrace their steps and make the survey back again, showing, this time, a rise of exactly the same number of feet as before, when they showed a fall. One hundred pounds per mile, Mr. Hampden [the anon. author of the pamphlet, referring to himself in 3rd person] is ready to give to any engineer or surveyor who will take him to any spot in the United Kingdom and show him the rise and fall according to the above table, as laid down in their own standard works. They dare not attempt it!

Mr. Wallace, in the recent survey, said he would take his stand below the top, and show an incline upwards of five feet at the end of the first three miles. Mr. Coulcher and Mr. Walsh say that he has done it; but they both state what is most palpably untrue! At either end of the six miles selected as the field of operation Mr. Wallace would have to prove the continuation of the decline in the proportion above stated. Could he have done this? Is any one so mendacious as to assert that he could? Let the reader bear in mind what is now said, that every statement that has been made with regard to these measurements will be found a tissue of the most daring falsehoods.

The idea of being "always on the top" is something so glaringly absurd that we fail to see its utter impossibility. Squirrels in a revolving cage, felons on a treadmill may be justly compared to these insane philosophers who dare assert and argue that every living man, woman, and child on a revolving globe are one and all "on the top." But the moment you compel these men to show you how they stand on the top, they immediately show a higher curve still! So, then, you find out it is not "the top" after all, but some distance below it, and you are only shown "the top" at a distance of some miles off. All, in fact, that they can do is to make yon look through a glass and say you fancy you see an horizon in the distance. Which horizon you can never reach; for as you approach it, it in turn sinks below "the top," and you see, or fancy you see, another horizon beyond. But the whole subject is so monstrous and fictitious that it. is vain to argue about what can never be proved, except in appearance. And of course snow can be made to look yellow or green by looking through coloured glass. But the snow does not change its colour, nevertheless.

External Quote:Mr Carpenter's "argument" exhibits a total ignorance of the use of the spirit level, and of the simplest principles of optics and geometry. We have three points taken, at equal distances, above what Mr C. maintains to be a true horizontal straight line--the surface of standing water. The eye is placed at one of the extreme points, and, looking at the other two points, they do not coincide, as they must do if in a straight line with the eye. Again, the cross hair in the telescope of the spirit level marks the direction of "the straight line at right angles to the plumb line at the point of observation" (as Mr C. very accurately defines the true level); and as the middle signal appeared considerably below this line, that alone proved that the water surface was not truly level. The distant signal being apparently as much below the middle signal as that was below the cross hair, is absolutely inconsistent with the three being in any straight line, still less with their being in the Carpenterian "straight line," but is perfectly consistent with the three being points in a circle of about the assumed radius of the earth. This is a question of elementary geometry about which there can be no dispute. I may add that the fact of the apparent "equality " of these distances (so dwelt upon by Mr C. in his "argument"), and the views from both extremities of the six miles agreeing so closely, both prove the very great accuracy of the level used, and that it may be depended on to show that the surface of water does really sink below the true level line in a continually increasing degree as the distance is greater; but the proof of convexity in no way depends on this accuracy, as it was shown still better by the large telescope without a spirit level.

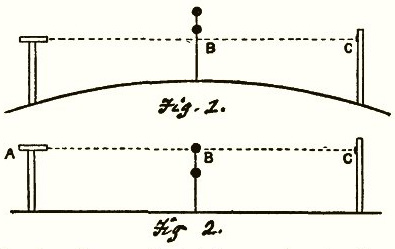

The top line establishes the astronomical horizon. Both targets are below the astronomical horizon. But no one should think about words such as below, or a rise or fall in the overly literal and rigid way Carpenter and Hampden did.External Quote:The lower curved line represents the supposed curved surface of the water. The points A B C are three points equi-distant above that surface. The top line from A is the level line shown by the cross-hair in the level-telescope. If the water surface had been truly level, the two points B and C must have been cut by the cross-hair. But even if the cross-hair did not show the true level, but pointed upwards, and the water was truly level, then the distant mark, being the same height above the water as the top disc at half the distance and the telescope, these two objects must have appeared in a straight line, the nearer one covering the more distant. It should appear on the straight line drawn from the eye at A through B, whereas it appears a long way below it, thus proving curvature, the essential point to be shown.

Thus the view in the large telescope and in the level-telescope both told exactly the same thing, and, moreover, proved that the curvature was very nearly of the amount calculated from the known dimensions of the earth...

At least three points is what I've been thinking. The more the merrier.If three points A, B, and C are the same distance above a water surface then if the water surface is flat then A, B, and C will be lined up when viewed from some point behind A.