Edward Current

Senior Member

After talking for a short while with someone who believes strongly in non-human intelligence on Earth, it often comes out that the person has had a life-changing experience witnessing something extraordinary. The object(s) described and the experience typically fits a pattern:

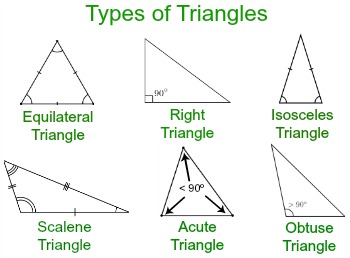

1. It often has a "TR-3B" description of a black triangle with lights, or some other triangular thing, occupying a significant portion of the sky, the experiencer getting a good look at it

2. It appears and leaves suddenly (rather than for example slowly advancing from the horizon)

3. The experience often happens at nighttime

4. The phenomenon is visual only — the "craft" and its flight are silent

5. The experiencer is too stunned and in awe to think of getting a picture or video, or it happened too fast, it was before cell phones, etc.

6. Sometimes the experiencer is in a small group (2 or 3 people) who share the experience and report seeing the same thing

7. Critically, no independent observers report seeing such an object

8. Critically, no land- or space-based device captures images or other evidence of such an object

In talking to these people, I am moved by their stories. The experience forever changes the way they see the world. However, except in rare cases, they are convinced that the thing they saw was real — it was a feature of objective reality, and would have been available to all observers at that time and place ("I know what I saw").

Additionally, there seems to be a strong distinction between this kind of up-close, astonishing experience and more generic sightings. The latter can happen at any time of day, and the object is always small or far away (SFA) and in the low-information zone (LIZ), and nothing prevents the witness from getting a picture. This tweet exemplifies the distinction:

Unfortunately these categories are often conflated, to where an "up close" experiencer is much more likely to believe that a SFA object in the LIZ is extraordinary, and they become intensely interested in the more mysterious cases like Gimbal.

These experiences affect people deeply, yet they are often brushed off by skeptics, including myself not long ago. I can empathize with experiencers' visceral reaction against the ECREE standard of skepticism: Experiencers have their own extraordinary evidence, and being disbelieved by others, having that personal evidence rejected, is not their problem.

To me it seems rather obvious what is going on. The least complication explanation, as well as the one with the greatest explanatory power, is that these experiences are unique to the experiencers. They are purely neuro-chemical in nature — they are not happening "out there," material or energetic objects perceived by the eyes and transmitted to the brain in the way that we see the Moon or lightning, but rather, they initiate in the brain. Perhaps there is a natural pharmacology involved, such as DMT or a related chemical (DMT occurs naturally in the body in small amounts). In the case of "my friend saw it, too," sociological factors such as peer pressure and the power of suggestion are at play — most dramatically, in the Ariel School sighting.

Now, you have to be careful approaching an experiencer with this hypothesis. In addition to "I know what I saw," the near-universal reaction is, "I'm not crazy" and "I wasn't hallucinating." A guy recently told me that he and his lady friend were on a rooftop in downtown Los Angeles and witnessed a giant UFO hovering over the city. He showed me a clip of his call in to Coast To Coast AM, imploring other people in L.A. at the time to come forward. And he got downright angry when I suggested it was anything other than an object in the sky at some altitude. It must be disturbing that such a life-changing experience cannot be corroborated by independent observers or devices.

I often bring up the Chelyabinsk meteor: Here was a once-in-a-century event, captured by enough dashcams from various angles, with enough clarity, to calculate the meteor's trajectory through the atmosphere to precision. But, how many giant-thing-in-the-sky experiences have individuals had over the years and decades? Not one of them has been corroborated by a single dashcam, cell phone, Ring camera, traffic camera, etc., etc.

You would think such questions would make an experiencer reconsider their conviction. Instead, it only cues heavily motivated reasoning.

We all want to believe that our perceptions and memories are an accurate reflection of objective reality. But the brain is a biological mess — extraordinarily complex, unpredictably unreliable and unreliably unpredictable, and subject to innumerable influences, both internal and external. It disturbs people that their perceptions and memories could be anything other than objective and accurate — something that can be seen in the popularity of social controversies such as the "Mandela effect" and "The Dress."

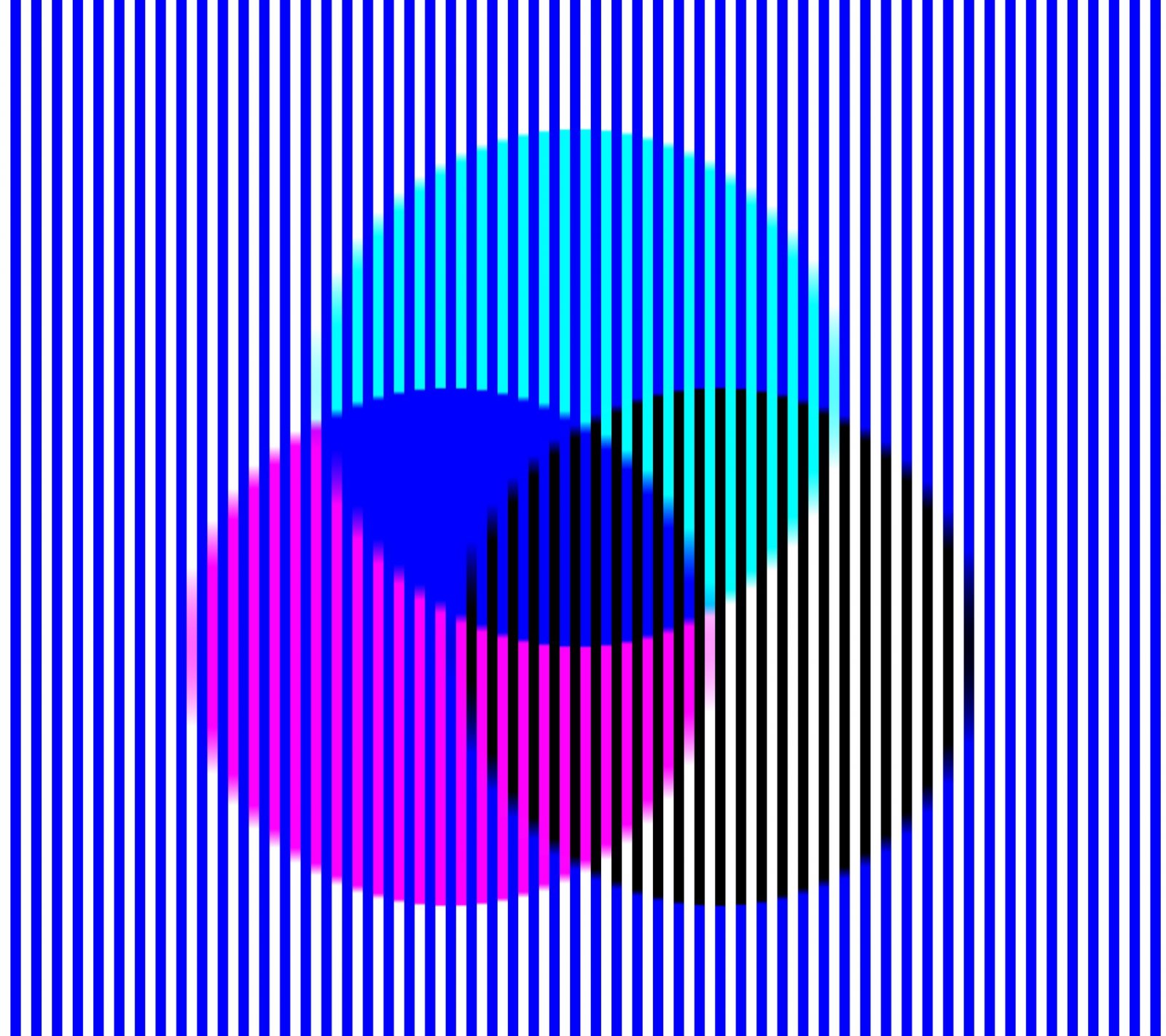

What's the best way to approach experiencers with this hypothesis? Are there illustrative examples that can help create a bridge to a common understanding? My go-to is usually an optical illusion, wherein I ask if they see yellow in this image:

...but it is a long way from a routine optical illusion to a giant life-changing triangle in the sky (they know what they saw).

This seems like a ripe topic for neuroscience research, and maybe it already is. But it's not like you can put someone having a UFO experience in an MRI.

1. It often has a "TR-3B" description of a black triangle with lights, or some other triangular thing, occupying a significant portion of the sky, the experiencer getting a good look at it

2. It appears and leaves suddenly (rather than for example slowly advancing from the horizon)

3. The experience often happens at nighttime

4. The phenomenon is visual only — the "craft" and its flight are silent

5. The experiencer is too stunned and in awe to think of getting a picture or video, or it happened too fast, it was before cell phones, etc.

6. Sometimes the experiencer is in a small group (2 or 3 people) who share the experience and report seeing the same thing

7. Critically, no independent observers report seeing such an object

8. Critically, no land- or space-based device captures images or other evidence of such an object

In talking to these people, I am moved by their stories. The experience forever changes the way they see the world. However, except in rare cases, they are convinced that the thing they saw was real — it was a feature of objective reality, and would have been available to all observers at that time and place ("I know what I saw").

Additionally, there seems to be a strong distinction between this kind of up-close, astonishing experience and more generic sightings. The latter can happen at any time of day, and the object is always small or far away (SFA) and in the low-information zone (LIZ), and nothing prevents the witness from getting a picture. This tweet exemplifies the distinction:

Unfortunately these categories are often conflated, to where an "up close" experiencer is much more likely to believe that a SFA object in the LIZ is extraordinary, and they become intensely interested in the more mysterious cases like Gimbal.

These experiences affect people deeply, yet they are often brushed off by skeptics, including myself not long ago. I can empathize with experiencers' visceral reaction against the ECREE standard of skepticism: Experiencers have their own extraordinary evidence, and being disbelieved by others, having that personal evidence rejected, is not their problem.

To me it seems rather obvious what is going on. The least complication explanation, as well as the one with the greatest explanatory power, is that these experiences are unique to the experiencers. They are purely neuro-chemical in nature — they are not happening "out there," material or energetic objects perceived by the eyes and transmitted to the brain in the way that we see the Moon or lightning, but rather, they initiate in the brain. Perhaps there is a natural pharmacology involved, such as DMT or a related chemical (DMT occurs naturally in the body in small amounts). In the case of "my friend saw it, too," sociological factors such as peer pressure and the power of suggestion are at play — most dramatically, in the Ariel School sighting.

Now, you have to be careful approaching an experiencer with this hypothesis. In addition to "I know what I saw," the near-universal reaction is, "I'm not crazy" and "I wasn't hallucinating." A guy recently told me that he and his lady friend were on a rooftop in downtown Los Angeles and witnessed a giant UFO hovering over the city. He showed me a clip of his call in to Coast To Coast AM, imploring other people in L.A. at the time to come forward. And he got downright angry when I suggested it was anything other than an object in the sky at some altitude. It must be disturbing that such a life-changing experience cannot be corroborated by independent observers or devices.

I often bring up the Chelyabinsk meteor: Here was a once-in-a-century event, captured by enough dashcams from various angles, with enough clarity, to calculate the meteor's trajectory through the atmosphere to precision. But, how many giant-thing-in-the-sky experiences have individuals had over the years and decades? Not one of them has been corroborated by a single dashcam, cell phone, Ring camera, traffic camera, etc., etc.

You would think such questions would make an experiencer reconsider their conviction. Instead, it only cues heavily motivated reasoning.

We all want to believe that our perceptions and memories are an accurate reflection of objective reality. But the brain is a biological mess — extraordinarily complex, unpredictably unreliable and unreliably unpredictable, and subject to innumerable influences, both internal and external. It disturbs people that their perceptions and memories could be anything other than objective and accurate — something that can be seen in the popularity of social controversies such as the "Mandela effect" and "The Dress."

What's the best way to approach experiencers with this hypothesis? Are there illustrative examples that can help create a bridge to a common understanding? My go-to is usually an optical illusion, wherein I ask if they see yellow in this image:

...but it is a long way from a routine optical illusion to a giant life-changing triangle in the sky (they know what they saw).

This seems like a ripe topic for neuroscience research, and maybe it already is. But it's not like you can put someone having a UFO experience in an MRI.