Additional analysis of 5,000+ year old granite jar suggest use of Turing machine.

A screengrab taken at 04:37 into the video linked to in Bill Ferguson's post

Can anyone explain what the circles are for- except to provide a symmetrical pattern superimposed onto the vase?

The central circle has a diameter the same as the broadest part of the body of the vase- and that's about it.

All the other circles are deliberately placed to intersect with the centre of the central circle.

Their centres are positioned along the circumference of the central circle, each 60 degrees along from its neighbours.

None of those 6 circles are centred on, or intersect with, any visible "landmarks" on the vase

(other than the centre of the middle circle, itself sited at the intersection of the "diameter" of the vase and the vertical axis).

The uppermost circles

almost intersect at the point where the lip of the vase angles back inwards towards the body of the vase, but not quite.

The six distal circles (inevitably) make a pretty six-petal pattern. But for what purpose?

What is the significance imparted by those circles? Is it meant to be an example of "sacred geometry"?

I'm not convinced that they tell us anything at all.

I've spent a few minutes knocking this together

(I don't have any special graphics software and did this by eye, obviously imprecisely)

External Quote:

Stephen Skinner criticizes the tendency of some writers to place a geometric diagram over virtually any image of a natural object or human created structure, find some lines intersecting the image and declare it based on sacred geometry. If the geometric diagram does not intersect major physical points in the image, the result is what Skinner calls "unanchored geometry".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_geometry

-This is

exactly what the "mystery vase" proponents have done!

At least

my circles intersect with the top of Mickey's snout and an ear...

-And Dr Skinner isn't some "explain-away-at-all-costs" skeptic; here's his Wikipedia page

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Skinner_(author)

Much is made of the fact that the vase is granite, which is physically hard to cut, but the ancient Egyptians left vast amounts of beautifully-worked granite. We know they had the tools, and the knowledge, because of all the obvious and impressive evidence.

The vase we're discussing looks like it has rotational symmetry. I don't think we can assess the tolerances of its finish from the images provided. I'm not sure the provenance of the vase is established beyond reasonable doubt.

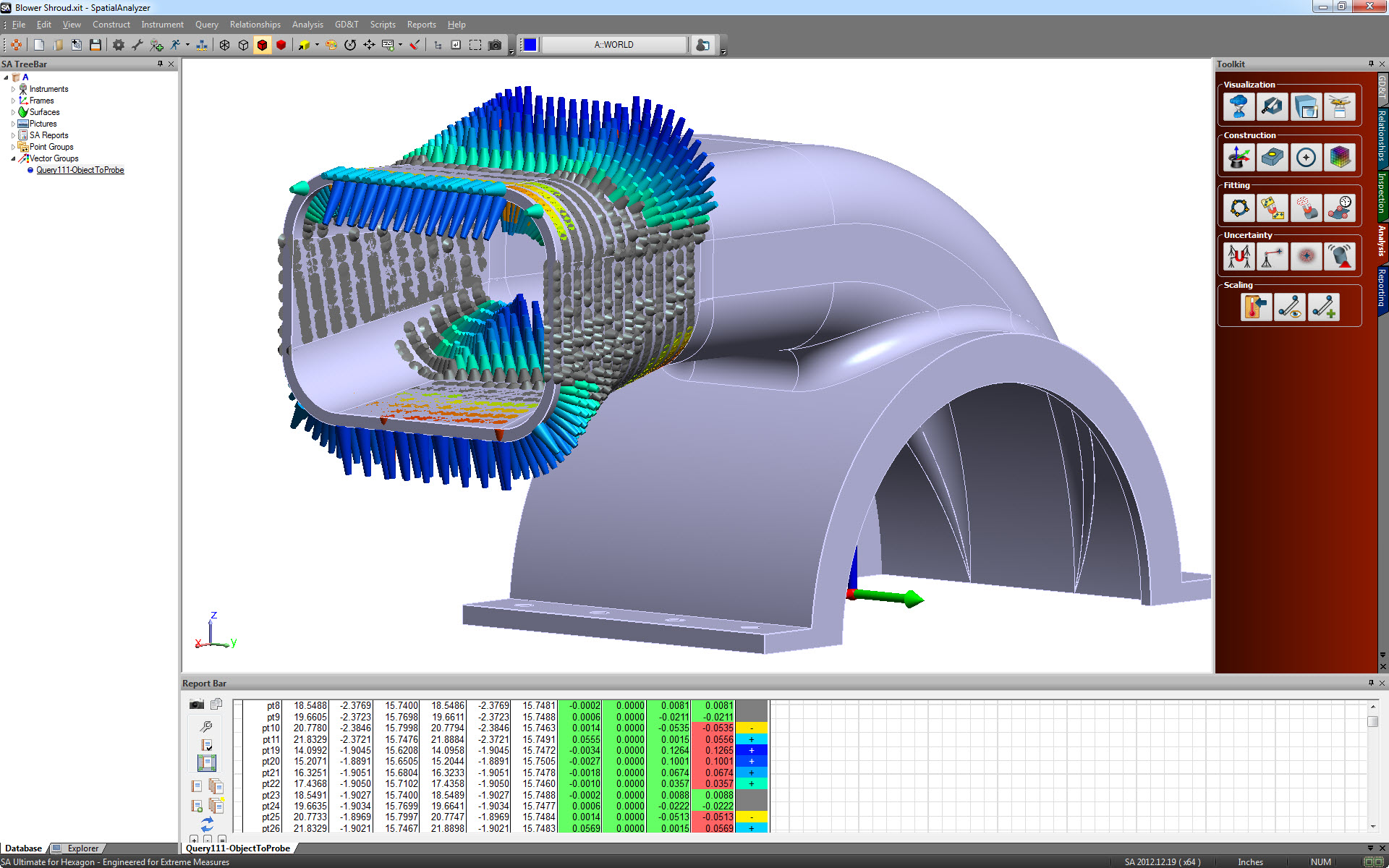

If the vase displays a level of precision that seems inexplicable unless CAD-CAM (or an equivalent technology) was used, why not take it to a university to have it examined and written up?

It doesn't have to be "surrendered" to an Egyptology department; I'm sure many materials sciences people would be only too happy to have a quick look. I don't know about these things, but I'd guess there's a LIDAR-type device that could scan the vase and give an accurate assessment of its rotational symmetry.

But the video- and the guys in it- don't give me much confidence. "Sacred geometry" is referred to a number of times as if it has a scientific foundation.

When telling us that the vase makers might have used "base Pi" or "base radian", the presenter tells us we use base 10.

Which we

do for most things- but our units routinely used for measuring angles are sexagesimal (base 60) in origin, and have their roots in the 3rd millennium BC in Sumer.

Which- considering what he's talking about- you might expect him to be aware of.

And the conclusions that the team draw- that the vase has a level of precision that requires a computer ("Turing machine" is incorrect) is, to put it mildly, extremely unlikely- though it's difficult to falsify their claims without having the vase examined by independent, relevantly-qualified people who are prepared to share their findings, including raw data.

The 200 inch mirror of the Hale telescope, Mount Palomar observatory, was designed and built

without the use of computers.

Ira Sprague Bowen, astrophysicist and 1st director of the Palomar Observatory, discussed the problems in mounting such a large, precise mirror:

External Quote:

Nevertheless, actual measurements show that with a simple three-point support, similar to that which is customary for very small mirrors, the flexure would be five hundred to one thousand times as great as the permissible value of a very few millionths of an inch.

(My emphasis).

From "

Final Adjustments and Tests of the Hale Telescope", I.S. Bowen, PDF here

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/126240/pdf

Wikipedia states

External Quote:

...the precision shape of the surface, which must be accurate to within

2 millionths of an inch (50

nm).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hale_Telescope, my emphasis.

If anyone thinks the vase is made to a greater precision than the Hale mirror, I very strongly suspect that they are mistaken.

It's a vase.

It hasn't been vital to measuring the red shift of quasars, or recording the spectrum of 'Oumuamua, yet by implication the guys in the video think the vase is a more complex artefact than the Hale mirror.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Until the vase chaps share their evidence (not their claims), there is no reason to accept their assertions.