NorCal Dave

Senior Member.

In a number of threads there is an ongoing discussion about Ancient Lost Civilizations that had, and possibly shared, any number of advanced technologies. The exact claims vary with the calamints. Graham Hancock has suggested a pre-neolithic civilization with a technology level similar to 19th century Europe, while YouTubers like Chris Dunn and Ben Van der Kerkwyk of Uncharted X claim ancient civilizations used Computer Aided Design (CAD) and Computer Numerical Control (CNC) devices similar to modern ones to create a variety of artifacts. For brevity I'll refer to the various proponents of Ancient Technology as ATs (Ancient Technologists) going forward.

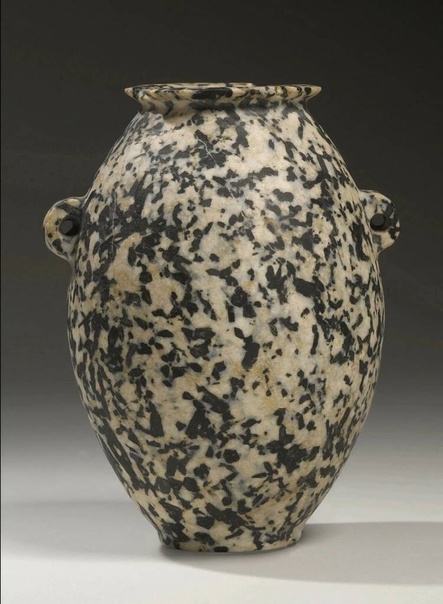

As none of these ATs have ever presented any physical evidence of the lost high-tech civilizations, the claims are often based upon circumstantial evidence, one of which includes a number of stone vases and bowls from early dynastic Egypt. The claim is that granite can only be worked with something much harder, like diamond and since many of these vases are made of granite, they could NOT have been carved by hand with the tools available to ancient Egyptians. They could only be made with modern multi axis CNC equipment. Many then also apply these same arguments to larger stones such as the blocks used in the construction of the Pyramids and other monuments.

In this thread we are only talking about the base level claim that Egyptians could NOT have worked or shaped granite as they had no diamond and were limited to copper tools. Discussions of design, pi relationships, and precision with which the vases were made, while important, is for other threads. Here we're talking about weather ancient Egyptians could shape granite with the tools they had and if so, what could the make.

This topic presents a bit of a conundrum, in that much of the claims and counter claims are in the form of videos, usually on YouTube. It makes sense, as a demonstration of ancient techniques is needed. However, some threads have devolved into competing YouTube videos being posted back and forth, so I'm going to try to reference videos where needed, but for flow and clarity I'll post all the relevant videos at the end.

The claim varies by clamant, but here I'll use Chris Dunn's version as a starting point (bold by me):

From the website Ancient-Code (bold by me):

Note the pressure supposedly needed. Numbers like these are often thrown out as evidence without really saying how. This includes the ATs obsession with the Mohs Scale, which we'll cover below.

This is Brian Forester's view on attempts to use ancient tools:

Here is Uncharted X saying that a small vase they claim is from pre-dynastic Egypt cannot have been made by hand. The history of this particular vase and the claims about the many other similar vases is best left to another thread. Using Closed Caption:

Just as a side note, 3 of the 4 sources above in addition to their YouTube channels offer a number of books and tours as part of their attempt to explain Ancient Technology.

The first thing to understand is that granite or other stones are not "cut". The term is used generically in construction and when installing something like granite countertops, one "cuts" the opening for the sink and "drills" the hole for the faucet. I'm not sure if ATs always just use the term "cut" in its generic sense, but it's a bit misleading when trying to understand how stone is worked.

All stonework involves grinding. The stone is ground away by means of an abrasive. This is different from cutting something like wood where some sort of teeth are used to tear out bits of the material. Here is a common saw blade and hole saw used in wood, aluminum and to a lesser extent metal:

Note the teeth that are used. I think ATs are content to let people imagine versions of these blades with diamond teeth that "cut" granite the way these blades cut wood. In contrast here is some of my stone "drilling" and "cutting" tools:

There are no teeth. There are gaps to let waste material get out, but no sharp teeth or points to "cut" the stone. Rather these tools grind the stone using abrasives embedded in them, which are clearly visible. These tools grind away the stone. The metal in both cases DOES NOT "cut" or grind the stone, it's only there to hold the abrasive and move the abrasive grinding agent through the stone. When one makes a straight "cut" in granite, one is actually grinding away the stone with a thin blade of abrasives in a line. Obviously, this blade is being spun at high speed by a power tool like this:

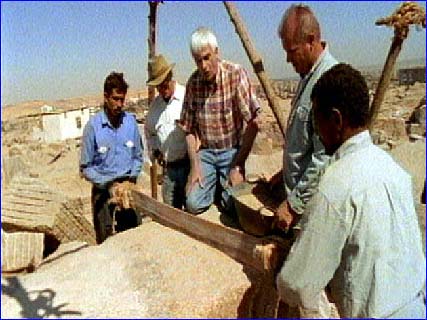

However, it's still just grinding the stone with an abrasive, something Denys Stokes has done using copper saws and sand on granite:

Stonemason Roger Hopkins also experimented with this technique, but added water:

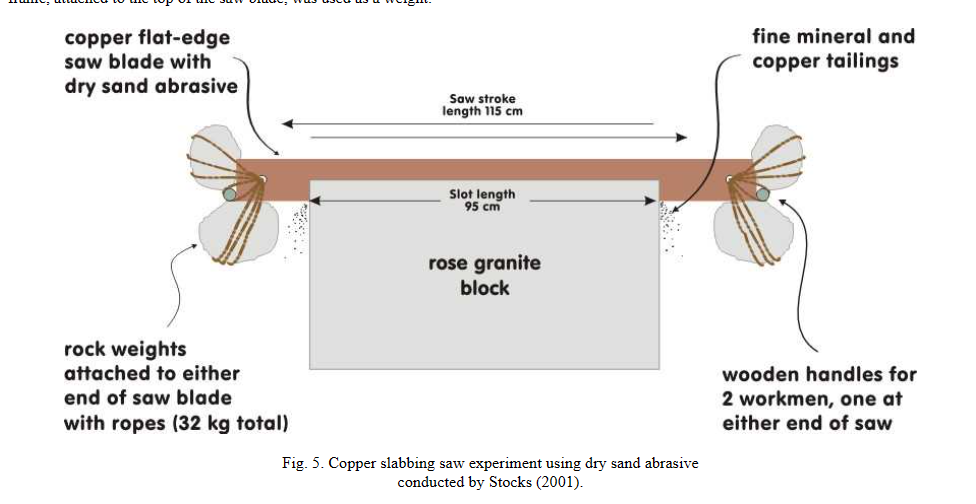

Here is Stocks' final saw design for large slabs:

In addition:

https://www.oocities.org/unforbidden_geology/ancient_egyptian_copper_slabbing_saws.html

The principle is the same in ancient times as in modern times, use a blade of some sort to move an abrasive through the stone and grind it away.

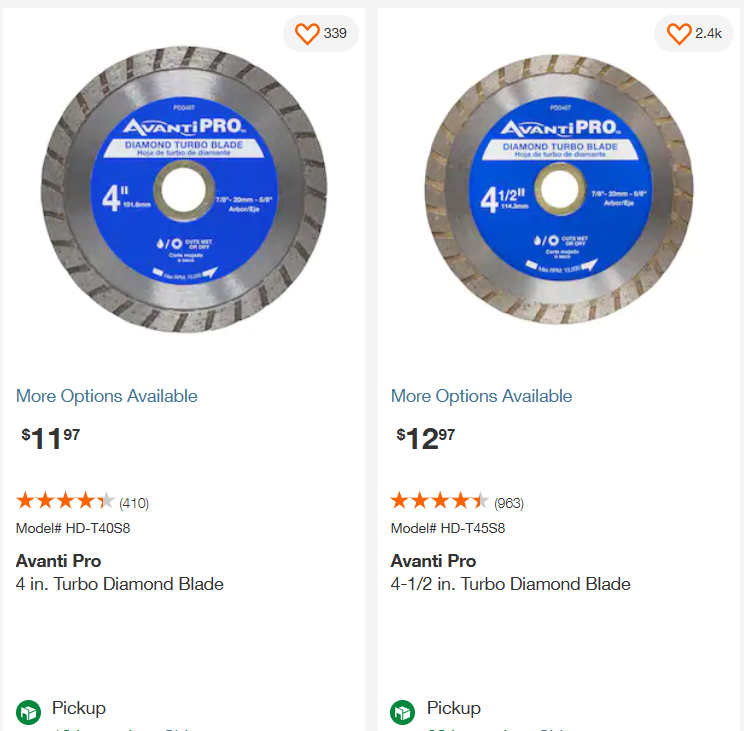

One can read "diamond" on the circular blade in the photo above and might think "Ah ha, diamond is needed to cut granite!". But, I'm not sure how much actual diamond is on these or if it's just the name they are sold under. It's a bit of diamond dust at best as these blades are typically between $10-$20 each:

In fact, these blades are coated with silicon carbide:

Silicon carbide is largely manmade and is some of it can be considered synthetic diamond:

So, maybe a bit of fake diamond.

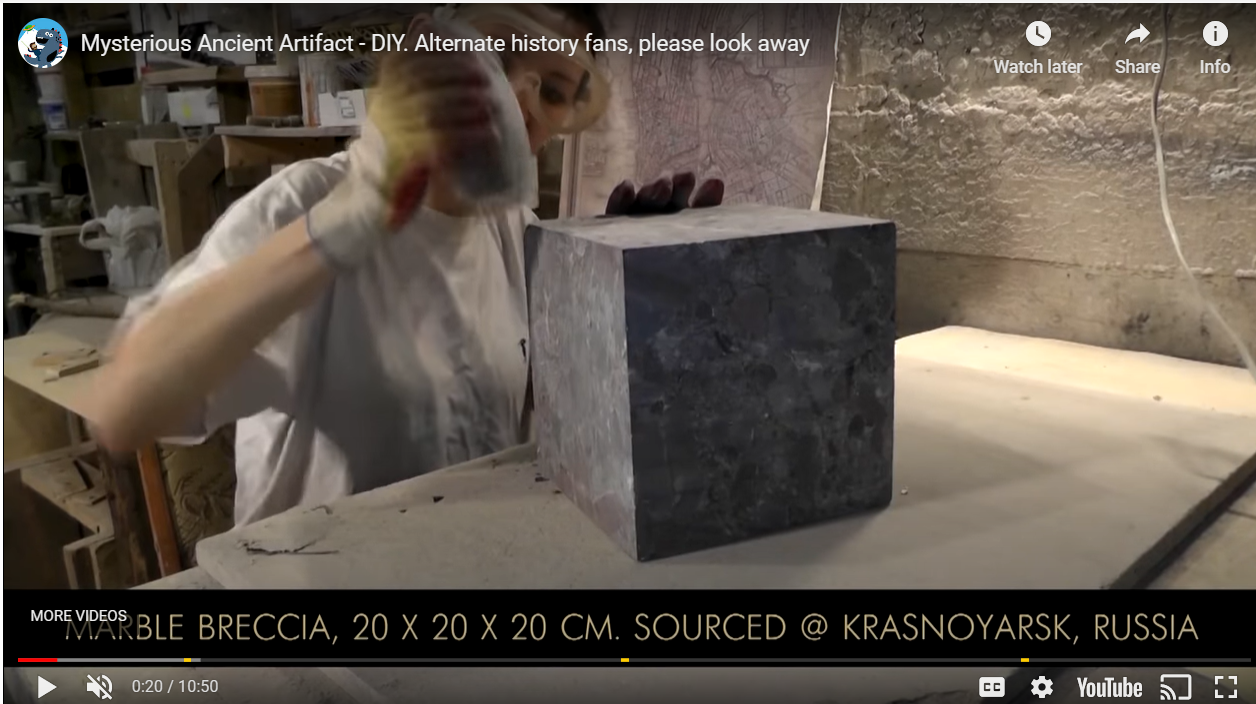

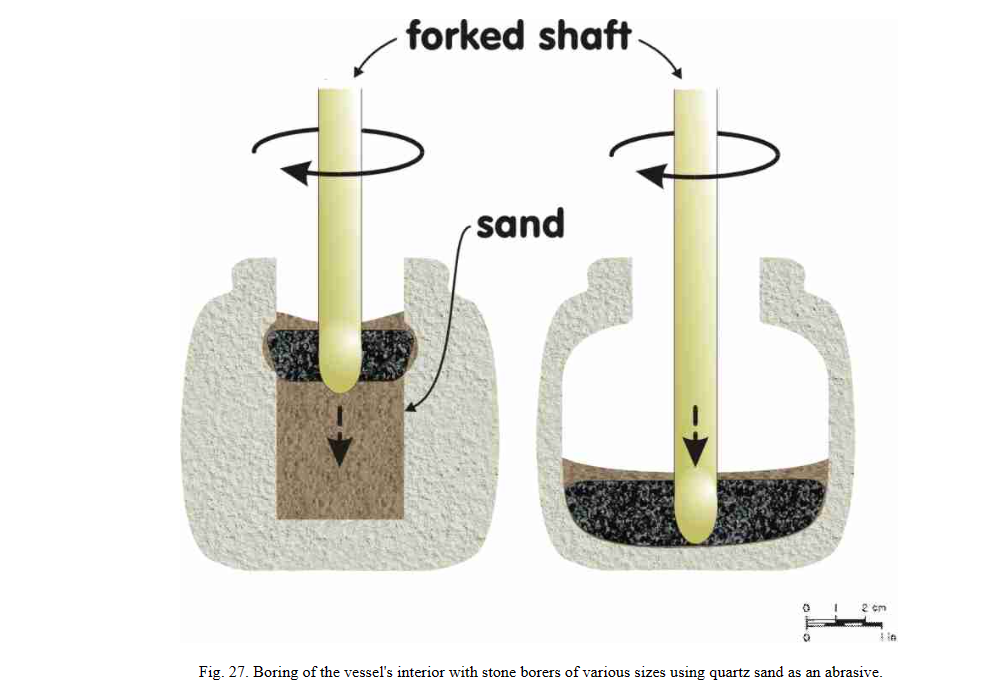

Same with drilling, here are the Russian guys from the Science Against Myths YouTube channel. They use a copper tube to agitate the abrasive in a circular pattern. The copper tube IS NOT "cutting" the stone, the sand is grinding the stone away.

And here is another form of drill used to hollow out a bird vase:

In addition to "cutting" with sand, stone can be worked with other stones. Some sort of hammer is one of the oldest tools used by early hominids:

Here is an artist using a stone to strike and shape another stone. Yes, this demonstration is being done on marble which is softer than granite, but like shapes like, so a granite hammer can do the same thing with granite:

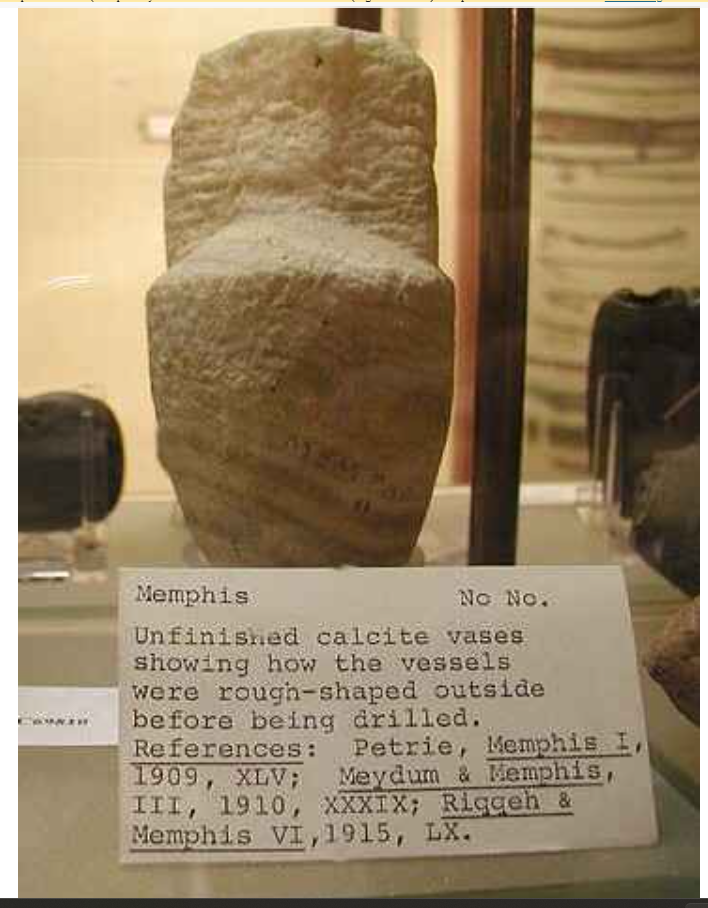

This "pounding out" technique is also consistent with the archeological record as unfinished vessels demonstrate:

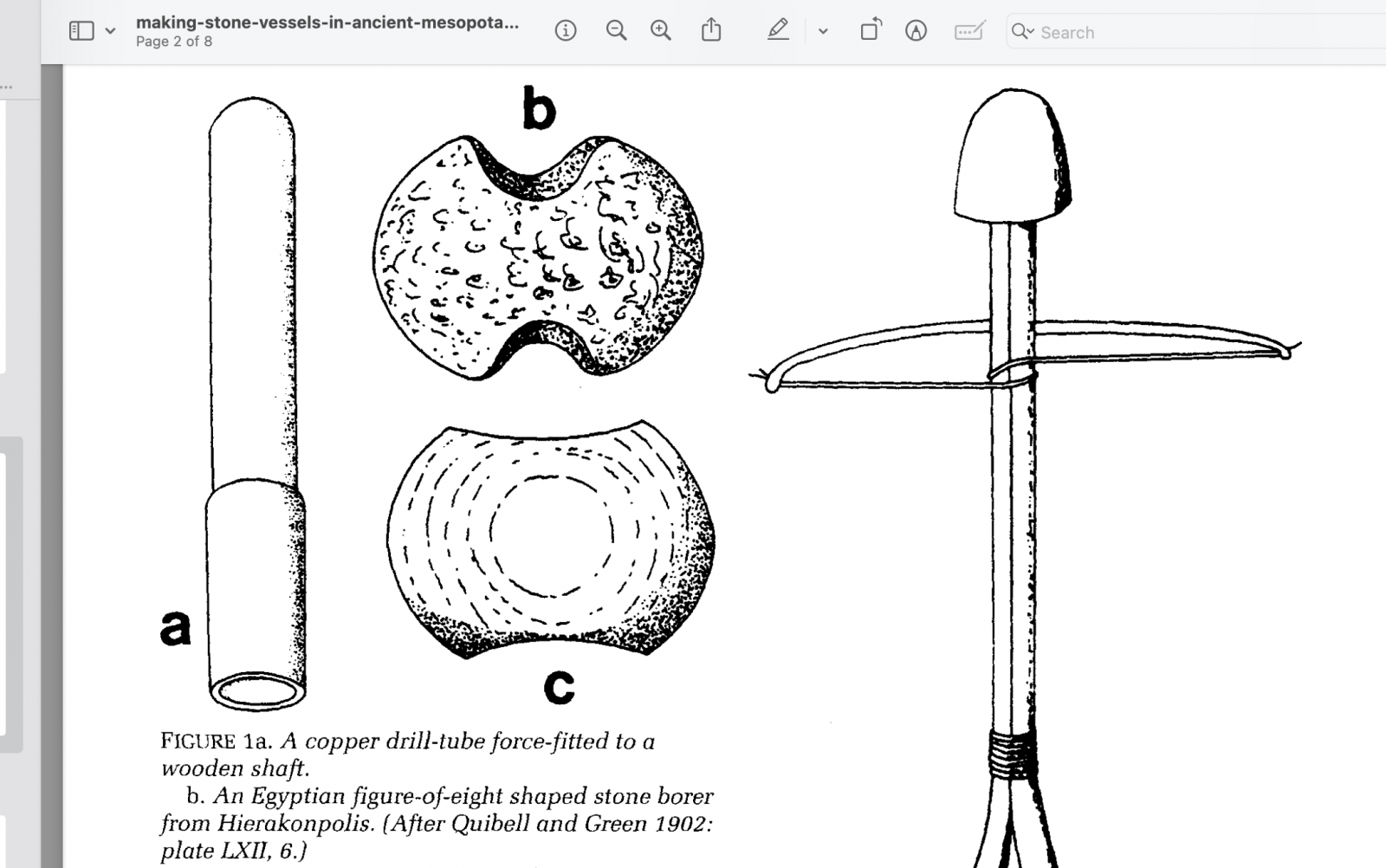

Other techniques can be used to shape stone as well. Stokes wrote a paper in the '90s where he experimented using a combination of found artifacts and pictures to create ancient type vessels. (Some of the content is from a PDF, so the formatting is wonky.)

STOCKS D. A., Making Stone Vessels in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, in Antiquity, A Quarterly Review of Archaeology 67, 1993,

Similar tools are found in ancient Mesopotamia:

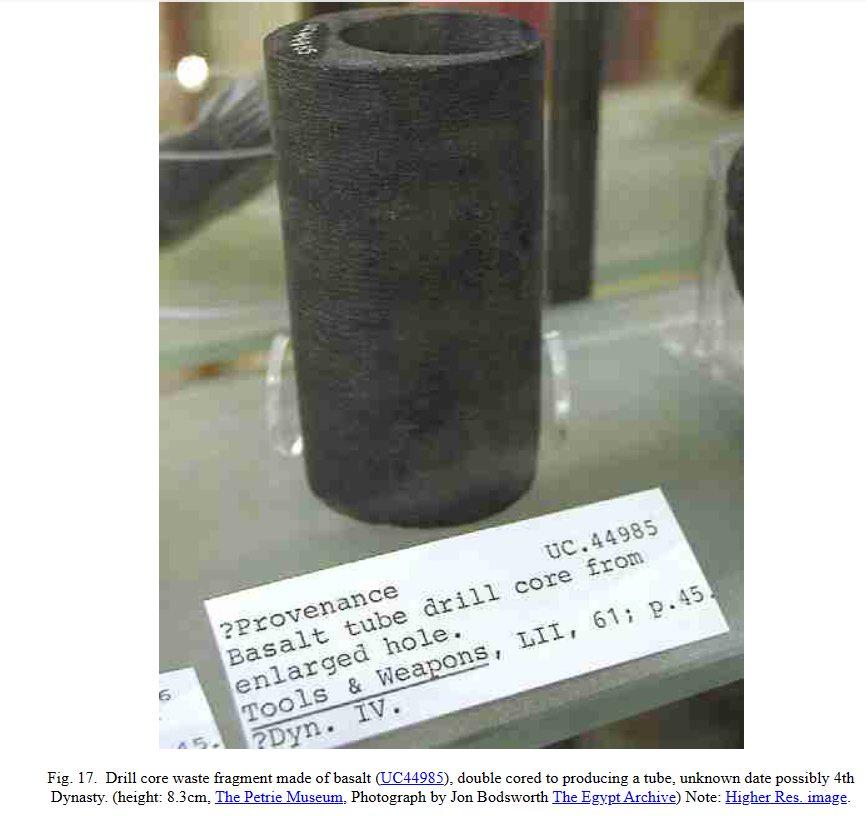

Multiple bore holes could also be used to rough out a vessel as these cores demonstrate:

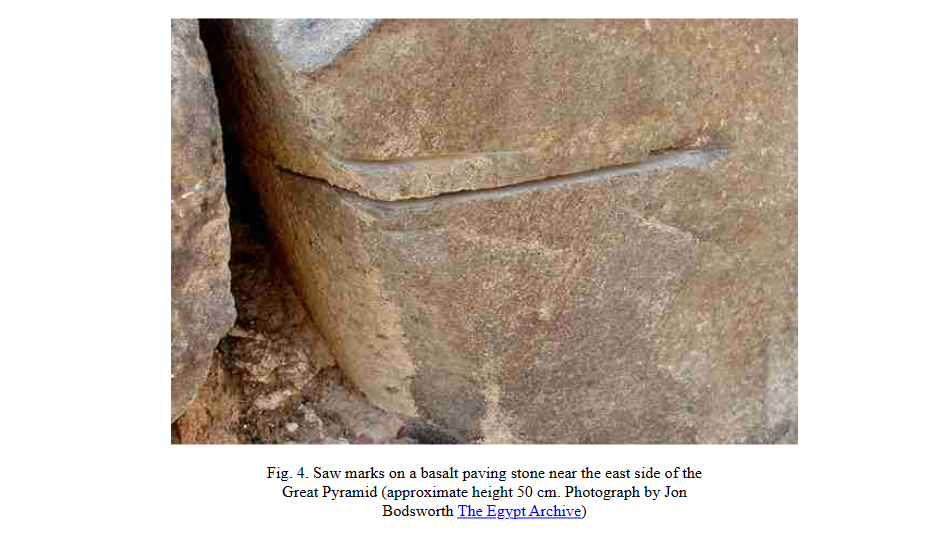

The AT crowd often mention the "machine marks" found on various artifacts, but these striations are consistent with ancient milling techniques:

Lastly is the obsession with the Mohs scale. The argument goes something like this: Granite is a 6 on the scale, so only something above a 6 can be used to shape granite. Diamond is a 10 on the scale, therefore diamond must be used to shape granite. Let's look at the scale:

Note that granite is not on there. That's because other materials are slotted into the scale:

Still no granite, because like most stone granite is a mixture of different minerals:

Nevertheless, note that if granite is often assigned 6-7 on the scale, quartz is a solid 7 and non-beach sand is largely made of quartz:

https://www.sandatlas.org/desert-sand/

In addition the Egyptians may have imported beachside black sand from the Mediterranean coast:

Zircon and garnet are 7-7.5 on the scale, so not diamond but hard enough to work granite.

I think there is ample evidence that ancient Egyptians could and did work various stones, including granite with the tools they had. Besides their tools, they had a long history of doing it and passing the craft on the later generations. I didn't even cover the use of flint, but I'll let others bring more examples and maybe get more specific on detailed techniques.

Some of the videos below, show conclusively, that vessels like found in ancient Egypt can be made by hand using ancient tools. How fast they could be made and how precise is for another thread.

This is the video of the guys using an ancient Egyptian drill:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyCc4iuMikQ

Here is the Russian artist making the bird vase:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mq2KGQajfAo

This is our Russian artist lady making a small vessel by hand with ancient tools:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC3Z_DBnCp8

Yet more ancient stone carving techniques using stone, copper, flint and other materials. No power tools needed:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fIigpabcz4

Here's a very poorly made video that's a bit hard to follow but has great information. He basically shows segments of Uncharted X and other videos, then counters them with actual hands-on experiments. Again, could have been much better done, but he does drill and shape some stone:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_iA3afiADw

As none of these ATs have ever presented any physical evidence of the lost high-tech civilizations, the claims are often based upon circumstantial evidence, one of which includes a number of stone vases and bowls from early dynastic Egypt. The claim is that granite can only be worked with something much harder, like diamond and since many of these vases are made of granite, they could NOT have been carved by hand with the tools available to ancient Egyptians. They could only be made with modern multi axis CNC equipment. Many then also apply these same arguments to larger stones such as the blocks used in the construction of the Pyramids and other monuments.

In this thread we are only talking about the base level claim that Egyptians could NOT have worked or shaped granite as they had no diamond and were limited to copper tools. Discussions of design, pi relationships, and precision with which the vases were made, while important, is for other threads. Here we're talking about weather ancient Egyptians could shape granite with the tools they had and if so, what could the make.

This topic presents a bit of a conundrum, in that much of the claims and counter claims are in the form of videos, usually on YouTube. It makes sense, as a demonstration of ancient techniques is needed. However, some threads have devolved into competing YouTube videos being posted back and forth, so I'm going to try to reference videos where needed, but for flow and clarity I'll post all the relevant videos at the end.

The claim varies by clamant, but here I'll use Chris Dunn's version as a starting point (bold by me):

https://www.gizapower.com/Advanced/Advanced Machining.htmlHaving worked with copper on numerous occasions, and having hardened it in the manner suggested above, this statement struck me as being entirely ridiculous. You can certainly work-harden copper by striking it repeatedly or even by bending it. However, after a specific hardness has been reached, the copper will begin to split and break apart. This is why, when working with copper to any great extent, it has to be periodically annealed, or softened, if you want to keep it in one piece. Even after hardening in such a way, the copper will not be able to cut granite. The hardest copper alloy in existence today is beryllium copper. There is no evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians possessed this alloy, but even if they did, this alloy is not hard enough to cut granite. Copper has predominantly been described as the only metal available at the time the Great Pyramid was built.

From the website Ancient-Code (bold by me):

https://www.ancient-code.com/abusir-evidence-advanced-technology-ancient-egypt/It is not a valid statement by Egyptologist that ancient people used handmade tools in order to create the mind-boggling drilling holes seen all across Abusir. It isn’t enough in terms of pressure and regularity. As website Revelations of the Ancient World explains, in order to cut granite today, a pressure on the drilling head of around 18-30lbs/sqi is needed. This is 226 to 380lbs of pressure for a 4-inch diameter drill hole.

It is hard –scratch that– it is impossible to think that this was achieved thousands of years ago by hand while holding handmade tools. The level achieved by ancient builders of Abusir is astonishing and can only be compared to modern-day machines.

Note the pressure supposedly needed. Numbers like these are often thrown out as evidence without really saying how. This includes the ATs obsession with the Mohs Scale, which we'll cover below.

This is Brian Forester's view on attempts to use ancient tools:

https://hiddenincatours.com/egyptia...ne-evidence-of-machining-before-the-pharaohs/In modern times we of course have diamond encrusted tube drills that can cut into hard stone, but the Dynastic Egyptians did not. Even though some academics theorize that the pharaohs had copper or bronze tube drills and used quartz sand as an abrasive, attempts at replicating the cutting process with such hand powered tools has been comical at best.

Here is Uncharted X saying that a small vase they claim is from pre-dynastic Egypt cannot have been made by hand. The history of this particular vase and the claims about the many other similar vases is best left to another thread. Using Closed Caption:

Just as a side note, 3 of the 4 sources above in addition to their YouTube channels offer a number of books and tours as part of their attempt to explain Ancient Technology.

The first thing to understand is that granite or other stones are not "cut". The term is used generically in construction and when installing something like granite countertops, one "cuts" the opening for the sink and "drills" the hole for the faucet. I'm not sure if ATs always just use the term "cut" in its generic sense, but it's a bit misleading when trying to understand how stone is worked.

All stonework involves grinding. The stone is ground away by means of an abrasive. This is different from cutting something like wood where some sort of teeth are used to tear out bits of the material. Here is a common saw blade and hole saw used in wood, aluminum and to a lesser extent metal:

Note the teeth that are used. I think ATs are content to let people imagine versions of these blades with diamond teeth that "cut" granite the way these blades cut wood. In contrast here is some of my stone "drilling" and "cutting" tools:

There are no teeth. There are gaps to let waste material get out, but no sharp teeth or points to "cut" the stone. Rather these tools grind the stone using abrasives embedded in them, which are clearly visible. These tools grind away the stone. The metal in both cases DOES NOT "cut" or grind the stone, it's only there to hold the abrasive and move the abrasive grinding agent through the stone. When one makes a straight "cut" in granite, one is actually grinding away the stone with a thin blade of abrasives in a line. Obviously, this blade is being spun at high speed by a power tool like this:

However, it's still just grinding the stone with an abrasive, something Denys Stokes has done using copper saws and sand on granite:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/lostempires/obelisk/cutting05.htmAs a young man, Denys Stocks was obsessed with the Egyptians. For the past 20 years, this ancient-tools specialist has been recreating tools the Egyptians might have used. He believes Egyptians were able to cut and carve granite by adding a dash of one of Egypt's most common materials: sand.

"We're going to put sand inside the groove and we're going to put the saw on top of the sand," Stocks says. "Then we're going to let the sand do the cutting."

It does. The weight of the copper saw rubs the sand crystals, which are as hard as granite, against the stone. A groove soon appears in the granite. It's clear that this technique works well and could have been used by the ancient Egyptians

Stonemason Roger Hopkins also experimented with this technique, but added water:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/lostempires/obelisk/cutting06.htmlHopkins' experience working with stone leads him to believe that one more ingredient, even more basic than sand, will improve the efficiency of the granite cutting: water. Water, Hopkins argues, will wash away dust that acts as a buffer to the sand, slowing the progress.

Adding water, though, makes it harder to pull the copper saw back and forth. While Hopkins is convinced water improves the speed of work, Stocks' measurements show that the rate of cutting is the same whether water is used or not.

Here is Stocks' final saw design for large slabs:

In addition:

The use of saws as a method of cutting rock is inferred from marks observed on ancient Egyptian stonework, including pieces of waste rock and finished and unfinished stone objects. Many of these marks have been found, usually observed as grooves cut into surfaces of rock or as striations on cut surfaces (Petrie 1974, Lucas and Harris 1962, Arnold 1991, Stocks 1999; 2001).

https://www.oocities.org/unforbidden_geology/ancient_egyptian_copper_slabbing_saws.html

The principle is the same in ancient times as in modern times, use a blade of some sort to move an abrasive through the stone and grind it away.

One can read "diamond" on the circular blade in the photo above and might think "Ah ha, diamond is needed to cut granite!". But, I'm not sure how much actual diamond is on these or if it's just the name they are sold under. It's a bit of diamond dust at best as these blades are typically between $10-$20 each:

In fact, these blades are coated with silicon carbide:

cutthewood.com/reviews/avanti-saw-blades-vs-diablo-saw-blades/This type of blade will be able to cut concrete blocks and natural stone. These blades are toothless and made of fiberglass-reinforced silicone carbide abrasive. These can cut blocks, brick, limestone, granite, concrete, marble and glazed ceramic tiles.

Silicon carbide is largely manmade and is some of it can be considered synthetic diamond:

Silicon carbide

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silicon_carbide(SiC), also known as carborundum (/ˌkɑːrbəˈrʌndəm/), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder and crystal since 1893 for use as an abrasive.

Because natural moissanite is extremely scarce, most silicon carbide is synthetic. Silicon carbide is used as an abrasive, as well as a semiconductor and diamond simulant of gem quality.

So, maybe a bit of fake diamond.

Same with drilling, here are the Russian guys from the Science Against Myths YouTube channel. They use a copper tube to agitate the abrasive in a circular pattern. The copper tube IS NOT "cutting" the stone, the sand is grinding the stone away.

And here is another form of drill used to hollow out a bird vase:

In addition to "cutting" with sand, stone can be worked with other stones. Some sort of hammer is one of the oldest tools used by early hominids:

A hammerstone (or hammer stone) is the archaeological term used for one of the oldest and simplest stone tools humans ever made: a rock used as a prehistoric hammer, to create percussion fractures on another rock.

https://www.thoughtco.com/hammerstone-simplest-and-oldest-stone-tool-171237Archaeological and paleontological evidence proves that we've been using hammerstones for a very long time. The oldest stone flakes were made by African hominins 3.3 million years ago, and by 2.7 mya (at least), we were using those flakes to butcher animal carcasses (and probably wood-working as well).

Here is an artist using a stone to strike and shape another stone. Yes, this demonstration is being done on marble which is softer than granite, but like shapes like, so a granite hammer can do the same thing with granite:

This "pounding out" technique is also consistent with the archeological record as unfinished vessels demonstrate:

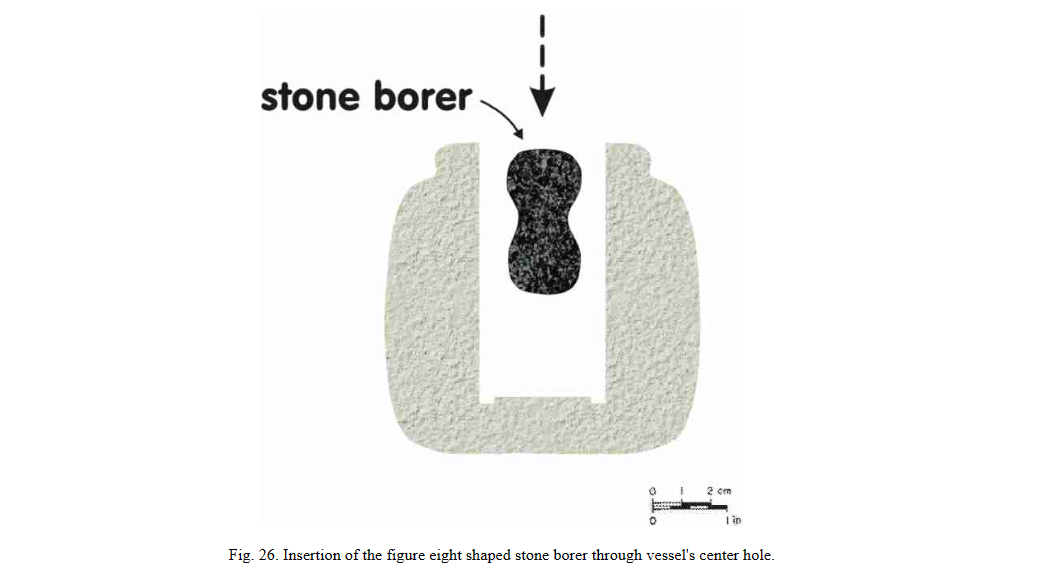

Other techniques can be used to shape stone as well. Stokes wrote a paper in the '90s where he experimented using a combination of found artifacts and pictures to create ancient type vessels. (Some of the content is from a PDF, so the formatting is wonky.)

STOCKS D. A., Making Stone Vessels in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, in Antiquity, A Quarterly Review of Archaeology 67, 1993,

In Egypt, this particular borer has

been discovered at Hierakonpolis, a site

associated with late predynastic and early

dynastic stone vessel production (Quibell &

Green 1902: plate LXII, 6) (FIGUREIb)

Similar tools are found in ancient Mesopotamia:

Here's how they worked:Circular borers were used to grind stone bowls whose interior was no wider than the mouth. A stone borer in the British Museum (BM 124498 from Ur), curved underneath and flat on top, has a piece cut out from each side of its upper surface, also for retaining a forked shaft. At Ur, stone borers were common in the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods

Multiple bore holes could also be used to rough out a vessel as these cores demonstrate:

The AT crowd often mention the "machine marks" found on various artifacts, but these striations are consistent with ancient milling techniques:

Striations on Mesopotamian vessels, and the bottom surfaces of stone borers, are similar to striations seen on their Egyptian counterparts - generally 0.25 mm wide and deep. Archaeological (e.g. BM 124498 borer from Ur; Petrie 1883: plate XIV, 7, 8; 1884: 90; Petrie Collection alabaster vase UC 18071) and my recent experimental evidence (Stocks 1998 111-36) strongly indicate that stone borers and copper tubes, were both employed with quartz sand abrasives.

Lastly is the obsession with the Mohs scale. The argument goes something like this: Granite is a 6 on the scale, so only something above a 6 can be used to shape granite. Diamond is a 10 on the scale, therefore diamond must be used to shape granite. Let's look at the scale:

However:The Mohs scale of mineral hardness (/moʊz/) is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

Though it can be used for milling:The Mohs scale is useful for identification of minerals in the field but is not an accurate predictor of how well materials endure in an industrial setting – toughness.[7]

Despite its lack of precision, the Mohs scale is relevant for field geologists, who use the scale to roughly identify minerals using scratch kits. The Mohs scale hardness of minerals can be commonly found in reference sheets.

The scale is made of 10 reference minerals:

| Mohs hardness | Reference mineral | Chemical formula | Absolute hardness[12] | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Talc | Mg3Si4O10(OH)2 | 1 |  |

| 2 | Gypsum | CaSO4·2H2O | 2 |  |

| 3 | Calcite | CaCO3 | 14 |  |

| 4 | Fluorite | CaF2 | 21 |  |

| 5 | Apatite | Ca5(PO4)3(OH−,Cl−,F−) | 48 |  |

| 6 | Orthoclase feldspar | KAlSi3O8 | 72 |  |

| 7 | Quartz | SiO2 | 100 |  |

| 8 | Topaz | Al2SiO4(OH−,F−)2 | 200 |  |

| 9 | Corundum | Al2O3 | 400 |  |

| 10 | Diamond | C | 1500 |  |

Note that granite is not on there. That's because other materials are slotted into the scale:

Below is a table of more materials by Mohs scale. Some of them are between two of the Mohs scale reference minerals. Some solid substances which are not minerals have been assigned a hardness on the Mohs scale.

Still no granite, because like most stone granite is a mixture of different minerals:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohs_scaleHowever, if the substance is actually a mixture of other substances, hardness can be difficult to determine or may be misleading or meaningless. For example, some sources have assigned a Mohs hardness of 6 or 7 to granite, but this should be treated with caution because granite is a rock made of several minerals, each with its own Mohs hardness (e.g. topaz-rich granite contains: topaz - hardness 8, quartz - hardness 7, orthoclase feldspar - hardness 6, plagioclase feldspar - hardness 6 to 6.5, mica - hardness 2 to 4).

Nevertheless, note that if granite is often assigned 6-7 on the scale, quartz is a solid 7 and non-beach sand is largely made of quartz:

https://www.sandatlas.org/desert-sand/

In addition the Egyptians may have imported beachside black sand from the Mediterranean coast:

https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/3/73719/Into-Egypt’s-Black-TreasureIn Egypt, black sand is available on the coast overlooking the Mediterranean Sea from Rasheed to Rafah with a length of 400 km. It is spread by sea currents and waves in those areas and present in the sand dunes.

Named after its color, black sand contains a percentage of essential minerals: ilmenite, zircon, magnetite, rutile, garnet, as well as monazite, which contains radioactive minerals.

Zircon and garnet are 7-7.5 on the scale, so not diamond but hard enough to work granite.

I think there is ample evidence that ancient Egyptians could and did work various stones, including granite with the tools they had. Besides their tools, they had a long history of doing it and passing the craft on the later generations. I didn't even cover the use of flint, but I'll let others bring more examples and maybe get more specific on detailed techniques.

Some of the videos below, show conclusively, that vessels like found in ancient Egypt can be made by hand using ancient tools. How fast they could be made and how precise is for another thread.

This is the video of the guys using an ancient Egyptian drill:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyCc4iuMikQ

Here is the Russian artist making the bird vase:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mq2KGQajfAo

This is our Russian artist lady making a small vessel by hand with ancient tools:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC3Z_DBnCp8

Yet more ancient stone carving techniques using stone, copper, flint and other materials. No power tools needed:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fIigpabcz4

Here's a very poorly made video that's a bit hard to follow but has great information. He basically shows segments of Uncharted X and other videos, then counters them with actual hands-on experiments. Again, could have been much better done, but he does drill and shape some stone:

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_iA3afiADw

but granite beads were made in Mali about a thousand years ago. You can buy them today - on Etsy.

but granite beads were made in Mali about a thousand years ago. You can buy them today - on Etsy.