https://www.metabunk.org/attachments/effects_of_choc-pdf.46180

Original: http://media.noetic.org/uploads/files/Effects_of_choc.pdf

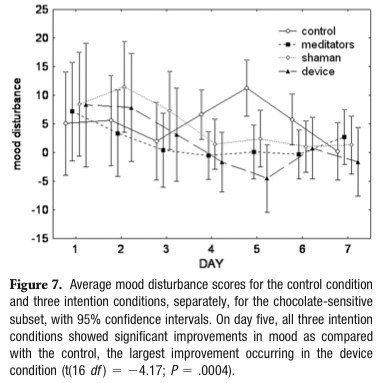

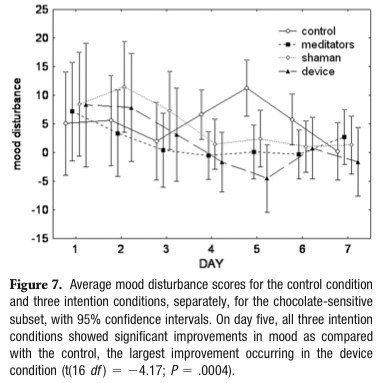

Scientists take chocolate, which is then blessed in various ways (by the mediators themselves, a Tibeten shaman, or an intention recording and playback device). The chocolate is then eaten for a week by four groups of 15 people, and their degree of mood disturbance is recorded every day. The results are pretty much the random walk you would expect from such small sample sizes.

On day five, some people in the control group were evidently having a bad day. The researchers take this as a significant result.

The "P-value" is basically the probability that the results might have been the result of chance, if all other variables are eliminated. The researchers ignore the facts that the groups were actually very different (inevitably, as there were only 15 people in each group), and experienced very different weeks. If you were to take 60 people in San Francisco at random, and separated them out into four groups of 15, you'd likely get very different groups. And a group of 15 (the control) is likely to vary more than a group of 45 (the average of the "intention" groups). So, yes, it is actually easily attributable to chance.

What really struck me though, was the extraordinary "get out of criticism free" clause at the end of the paper.

So in order for the experiment to work:

Basically, every time the experiment does not work - then it's because someone was skeptical, somewhere in the world, and possibly hundreds of years in the future.

Original: http://media.noetic.org/uploads/files/Effects_of_choc.pdf

Scientists take chocolate, which is then blessed in various ways (by the mediators themselves, a Tibeten shaman, or an intention recording and playback device). The chocolate is then eaten for a week by four groups of 15 people, and their degree of mood disturbance is recorded every day. The results are pretty much the random walk you would expect from such small sample sizes.

On day five, some people in the control group were evidently having a bad day. The researchers take this as a significant result.

The overall intention versus control difference on day five resulted in a modest P=.04, which which is not particularly persuasive. However, the same comparison for the preplanned subset of people who did not habitually eat much chocolate resulted in P = .0001. This is no longer easily attributable to chance, even given the small sample size of the experiment. Other conventional expla- nations do not readily come to mind.

The "P-value" is basically the probability that the results might have been the result of chance, if all other variables are eliminated. The researchers ignore the facts that the groups were actually very different (inevitably, as there were only 15 people in each group), and experienced very different weeks. If you were to take 60 people in San Francisco at random, and separated them out into four groups of 15, you'd likely get very different groups. And a group of 15 (the control) is likely to vary more than a group of 45 (the average of the "intention" groups). So, yes, it is actually easily attributable to chance.

What really struck me though, was the extraordinary "get out of criticism free" clause at the end of the paper.

Future efforts to replicate this finding should seriously consider sources of intentional enhancement and contamination that might influence the postulated effect. On the enhancement side, we recommend that the intentional imprints be provided by highly experienced meditators or other practitioners who specialize in tasks requiring intense, prolonged concentration. In addition, both the participants and investigators should ap- proach this experiment critically—but genuinely open—to the hypothesis. Although it is necessary to maintain a skeptical stance in science, persons holding explicitly negative expectations should not be allowed to participate for the same reason that dirty test tubes are not allowed in biology experiments; if one is testing the role of intention, then vigilance is required about the intention of all individuals involved in the test. This would extend to people who are aware of the experiment but are not otherwise involved; it may even extend to people who learn about the experiment in the future after the study is completed. Given theoretical support and experimental evidence for retro-causal effects replication of intentional phenomena may be inherently limited because once conducted and published, an experiment might be influenced by a potentially infinite number of future intentions (this divergence problem is only a serious problem if intentions of all observers have the same impact, eg, see Houtkooper56). Analogous to taking a flash photograph of an object in a hall of mirrors, in this realm it may not be possible to completely eliminate all sources of contamination.

So in order for the experiment to work:

- All partipants must believe it works

- Everyone aware of the experiment must believe it works (even if they don't participate, or are even nearby)

- You must tell nobody skeptical about the experiment in the future, or their skepticism will travel back in time, and negate the results.

Basically, every time the experiment does not work - then it's because someone was skeptical, somewhere in the world, and possibly hundreds of years in the future.

Attachments

Last edited: