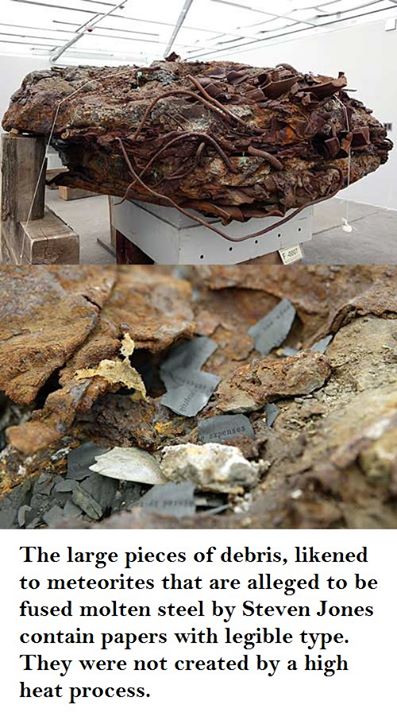

Glowing hot steel beams are easily identified within the rubble and their color is a good representation of their temp.

This might be an old thread, and perhaps what I am about to mention has already been addressed, but looking at the colour of glowing substances

through an image taken by a camera is not a good way to analyze temperature at all. I recently had this very discussion with someone, and I made an image to illustrate the problem.

Identifying temperatures by colour/intensity is something that you do with your eyes. This is because most eyes are the same. They have the same colour perception and dynamic light range, which is more than even current high end cameras.

Camera's limited dynamic range and white balance cause colour information to be distorted, especially in digital photography.

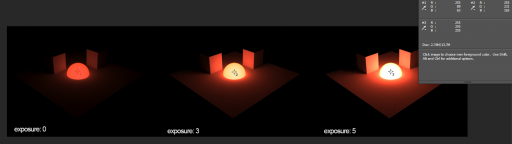

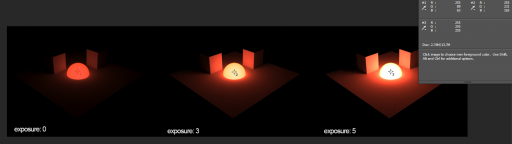

Here is a simulated scene of a perfect blackbody (meaning all the light comes from the object itself).

Note that the hue of the glowing object on the left is red. But look what happens when we raise the exposure value, essentially making the image brighter. The glow turns from red to orange-yellow. Please remember that we did

not change the intensity of the glowing object, just the exposure of the camera. Raising the intensity of the object while remaining on the same exposure value would yield the same effect, but in the real world it is usually the camera exposure that changes, not the intensity of the object.

So why does the colour change from red to orange-yellow from a mere exposure change despite that they underlying hue of the glow remains unchanged? Here is when the limited dynamic range of most cameras play tricks on us.

Watch the RGB values at the top right. All of them samples a 5-by-5 pixel area.

Sample #1 got an RGB value of [255, 89, 63].

For 8bit images (most consumer cameras today still shoot in this resolution) 255 is the maximum value for each channel. So an RGB value of [255, 0, 0] will yield a pure (absolute) red colour.

Making an absolute colour brighter is impossible with 8bit colour data (which is based on integer values), because there is no green or blue hues in there to be raised and move the luminance closer to white. One need to add to both the green and blue channel to move the luminance close to white, since pure white is [255, 255, 255].

In the real world there are no absolute colours like this, at least not in our everyday situations. Most conventional light sources (including glowing metals) will always contain traces of green and blue when captured on cameras with limited dynamic range.

So in my example, the only possible, and at the same time logical thing that happens when we change the exposure is to introduce more green and blue. The exposure (sometimes also called

gain) will multiply the existing values.

So sample slot #2 shows that the only way to make the red glow brighter is to raise the values of the other channels, mostly green in this case. This leaves us with a orange-yellow hue instead of the original red.

My example is created using a virtual camera simulating optic phenomena, but you get the same effect when photographing glowing things with a real camera and store the image in a limited dynamic range format.

On top of that you have the camera's white balance, which can severely distort hues of light.

So the thing about identifying temperature by colour and intensity becomes meaningless when just looking at a JPG-image you downloaded from the internet.