Debunking, according to Merriam Webster’s Dictionary

Debunking is NOT about taking one side of an argument, and then using whatever means possible to convince someone that you are correct. A good debunker is a good scientist. If there’s information that contradicts your position, then don’t ignore it, instead you should alter your position.

It’s not us vs. them. Invite everyone to point out errors in your facts, or in your reasoning. Focus especially on facts. Ideally you would be able to present enough verifiable facts that any reasonable person would come to the right conclusion.

There are various kinds of audiences you should have in mind when writing a skeptical article.

The easiest to write for is a community of like-minded skeptics. This is essentially preaching to the choir. It’s intellectually satisfying, but not terribly useful. These people are already immune to bunk, and at best this will be bolstering their immunity, maybe contributing somewhat to herd immunity. But really not a lot. The believers in bunk do not read Skeptic Magazine.

Then consider writing a generally accessible article for those people who have not formed a strong opinion, but are familiar with the subject matter. The “what’s up with that mystery missile story” people. This is also fairly easy, as you can generally just lay out the facts. Providing you can communicate reasonably, then things should work out fine. They are healthy people with enquiring minds. They may not have all the facts, but if given all the facts, they should be able to come to a reasonable conclusion.

Then there is writing for people who have no idea what the problem is in the first place. Like if you were asked to write a “chemtrail” article for USA Today, a popular American newspaper. Since the vast majority of people have not heard of chemtrails, you have to actually explain why people believe in them in the first place, and then explain what the problems with the theory are. This is analogous to inoculating them with a weak or dead form of the theory, and then letting their natural rationality take care of it, and hopefully build up some immunity to this and similar theories.

Then you descend to the various levels of bunk infection. There are a few levels worth noting here.

There’s the reasonable believer. They believe the theory, but they do so based on what they think are facts. They can be open to new facts, and can often be rescued. Be aware that they will have several infections of bunk, and you are not going to get rid of all of them. Don’t try to. Don’t even discuss the stronger bunk infections if possible. You can talk them out of chemtrails, and maybe the moon landing hoax, but 9/11 might be a bit too far. One step at a time.

Then there’s the “true believer”. The True Believer has lost all immunity to a particular subject. Anything you say that contradicts their belief must be a lie, because it contradicts a true belief. You need to establish common ground somehow, and work from there. Frequently they will not see reason, but they can be useful as a source of memetic material to help inoculate others. They will frequently run through the entire set of “evidence” one piece at a time, oblivious to the fact that everything they bring up is easily explained. This is useful simply for you to get familiar with the arguments used.

Then you have the extremists. People beyond the reach of reason, who don’t even have a good basis for their own beliefs. The lack of rationality in their arguments makes them both impossible to reason with, and basically useless for any part of debunking (except perhaps to illustrate how extreme the argument is - but that’s not a very good argument in itself, something of a fallacy). Best to ignore them, and hope they go away.

Tell the Truth

Don’t lie. Lies are evil. Lies will come back to hurt you. Lies are wrong. Don’t lie.

Don’t hide facts. If something conflicts with your theory, then change or expand the theory. If you hide a fact, it’s going to come up later. Be honest now, and you’ll be safe later.

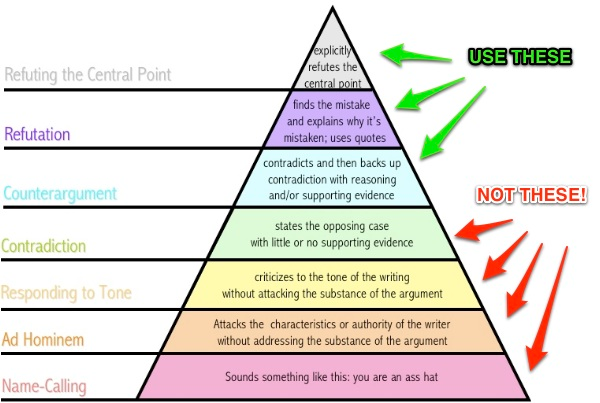

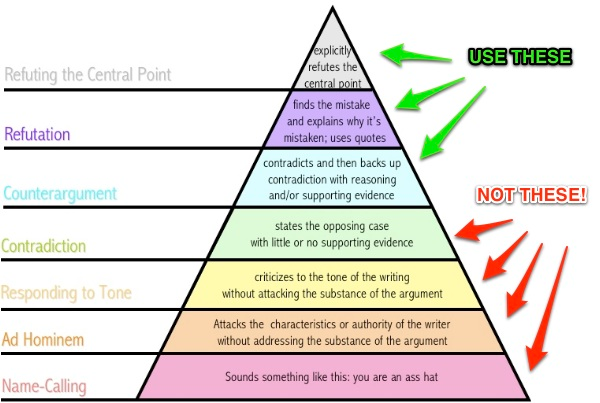

Be polite.

Insulting people just polarizes them. Even perceived insults will have this effect. Telling someone they are “stupid”, “retarded”, or even that they “need to do more research”, is entirely unhelpful to progress. We are trying to get out the bunk, and if you insult people then they will just cling to their bunk tighter.

Of course there will be people who reject your ideas, no matter how you present them, polite or not. But always remember you have a greater audience than the person you are ostensibly discussing with. Part of that greater audience might be convinced, even if the individual is not.

Have a Thick Skin

People will insult you. They will call you stupid, evil, ignorant, a shill. They might even threaten you. Do not let this get to you, and do not let it tempt you to respond in kind. Being perceived as angry will only provide a distraction from what you are saying.

Don't be passive-aggressive

And don't be sarcastic. It's all stuff that can be perceived as insults, and all stuff that can distract. Instead be simple, honest, direct, and polite. Take a deep breath. If you feel venom as you are typing, it will probably come though in what you say. Be polite. Be nice. Do it honestly.

Don’t try to win

Don’t compromise truth for the sake of "winning". It’s not a contest. You don’t win if you convince someone of your point of view, but lie to them or withhold evidence along the way. You don’t win by bullying them with facts until they run away. You want a mutual agreement, something where both of you have arrived at a commonly held understanding of the facts that is closer to the truth. This might even mean you yourself may change your opinions a little. But that’s why they are just opinions.

Don’t be an expert

It does not matter what your credentials are. Don’t assume that makes you right. Being an expert gives you easier access to information, and it provides mental tools to help process that information. But you can’t just then say “because I say so”. You still have to explain, to demonstrate, and to provide the means of verifying your point of view.

Keep on target

One thing at a time. It’s very important to not lose focus, as there are lots of topic out there that will suck the life out of any discussion. One can be having a perfectly reasonable discussion about why contrail cirrus can last for several hours, and then someone says “yeah, I suppose you believe that WTC7 fell down because of a little fire”, and all of a sudden it’s tangent city. Of course you could fully debunk any WTC7 myth they throw at you but don’t go there. It’s just a huge time sink. Don’t allow off-topic discussion if possible, and just ignore it if you can’t.

Know Your Limits

Don’t dive into a highly hostile forum that has deep and bunk-filled views of the world. If they all agree, then you are going to get nowhere. There has to be at least some discussion going on there already, or some air of reason, for you to do anything productive. There’s a range of conspiracy forums. They all contain the full spectrum of conspiracy theorists, but some forums tend more towards the extremes than others . Read before writing there. Above Top Secret is more sensible than Prison Planet. Prison Planet is more sensible than David Icke. David Icke is more sensible than some of the more specialized forums out there.

Debunker or Skeptic?

Both, of course. But beware of language. For some “skeptics” are evil minionions, for other it’s “debunkers”. They have somehow got the wrong definition of the word. I hesitated somewhat in using “bunk” at all in this blog. But then it’s for people who understand what true scientific skepticism is, and what true debunking is. But you might want to be careful in an initial encounter not to alienate people by saying you are a “debunker”, if you know they are going to take that the wrong way. If you do describe yourself as a debunker (which I prefer), then make sure you can take the time to explain what it means. Debunking is just removing bunk - what do they want, you to leave the bunk alone?

Citation Needed

Back up your assertions. Provide the source of your data. Don’t just say “Aluminum makes up 8% of the Earth’s Crust”, unless you can back it up. If you are writing an article, then cite as many authoritative sources as possible. If it’s a comment, or in a discussion, don’t claim something unless you can quickly provide evidence of it.

Keep it simple

It’s not simple. It’s complicated. It’s very easy to make the explanation complicated, and then you either lose them by using science beyond their ken, or you get bogged down in minutiae. Keep it simple. “It can’t be true because … [of this one thing]”. Use the simplest thing that you think they will understand.

Quick example there - The Bard of Ely believed in chemtrails, and fought against all arguments. The breakthrough came when he realized that the solar halos could only be made by ice crystals, not powder. Unfortunately there’s no way of knowing that that was the one thing that would tip the balance.

Let them debunk it for you

Teach a man to fish and you won’t need to keep giving him fish. While it’s very temping to simply lay out the facts and prove that something is bunk, it’s much more productive for everyone to allow them to fill in a few steps for themselves. You need to gauge this carefully. Many people “want to believe”, so will resist doing anything that might harm their beliefs. But if you can get someone to look something up, perform a simple experiment, or fill in a logical step in an argument, then you win them over in a far more solid manner than if you did all the work for them.

You can extend this by actually teaching them how to debunk - or at least giving them little skills, like how to effectively use Google, or perhaps some little bit of math, or a reference they can use.

Know the Language

Believers often have a very specific usage or misunderstanding of specific terms. They frequently take any mention of some term (e.g. “aerosol”) to be related to their specific theory. Understand this when discussing the subject with them, and attempt to either explain what the term means, or use more neutral terms (dust, water vapor). Sometimes they will pick on an unusual phrase and simply misinterpret it, like “radiative forcing”. Here you’ve got to explain the term to them. You’ll have to do it again and again. You might want to consider putting up a little glossary of frequently misunderstood terms for your domain.

Don’t trust their eyes

Quite often you get statements like “I know what I saw”. When what they saw was something fairly boring, but it looks like something, and then they fit that into their world view. These types of things can be neatly described by:

A) Looks like: (something suspicious)

B) Hence: (How that fits into their world view)

C) But: (What it actually is)

A good example being the “Fema Coffins”:

A) Looks like: thousands of over-sized coffins stored in a field

B) Hence: FEMA must be planning to kill thousands of people

C) But: It’s actually just coffin liners

The cognitive dissonance occurs because for the believer it’s a lot simpler to go with A and B than to incorporate some new information C. They already “know” that there’s this huge population reduction conspiracy going on, so A and B fit that perfectly. C is new information that works against the conspiracy, so must be false.

Keep it Understandable

The most irrefutable debunk in the world is useless if nobody reads it. It needs to be written in an accessible manner. Give the simplest and easiest to check facts first. Make it entertaining. Politeness is a factor here again, as you can turn people off. Be polite, and more people will read it.

Use simple language. Use short sentences. Encapsulate single concepts in single paragraphs. Don’t include confusing things unless needed. Leave those to a sidebar/appendix/footnote. Keep it along the lines of “Because A, then B”.

Learn from History

Where did this conspiracy come from? What is the context? The fluoride conspiracy makes more sense in the context of the communist fear period of McCarthy in the 1950s. So what are the Zeitgeistical roots of this conspiracy? Chemtrails come from health scares on talk radio. UFO’s come from the Roswell incident and the Red Menace. The Federal Reserve conspiracies perhaps from anti-semitism.

Avoid repeating yourself

Think twice, write once. Make your explanations well worded, and in a form that can be re-used. It’s better to put some effort into writing a blog post, because then whenever someone raises the same point again, you can just point them at the post (I really should write a post explaining Radiative Forcing). If new information comes along, you can just update the post.

Avoid Repeating Others

Unless you are debunking a niche theory, then it’s likely that other people will have addressed any given point before, and often very well. If there’s a better explanation, then just link to it. If there are multiple explanations, then link to them. If you find you have to write additional material, then you might need to synthesize the various other articles into something new. But make sure that you are adding something. Make a copy of whatever you link to, in case it vanishes.

Don’t debunk where there is no evidence

A very common problem in bunk circles is when they raise the issue “you can’t prove that it isn’t”. Do not rise to this bait. The key point is that they have no evidence that it is. There are an infinite number of things that you can’t prove are not so (see: Russels Teapot), so for them to require you to debunk something, they first have to provide evidence that it IS so. Then your first step it to nullify that evidence by explaining it with conventional theories (long lasting trails in the sky = contrails). One their evidence is nullified, you don’t need to provided extra evidence against their theory, as they now still have no evidence for it. You are a debunker. The bunk here is the evidence and the reasoning they use. Remove that bunk and all you have is a random theory.

“To expose the sham or falsehood of a subject” l.P.

When you debunk an assertion, you are demonstrating that some of the reasoning, or the claimed facts, behind that assertion are false. You look and see what they are claiming, you identify which bits are true and which are not, then you explain this.Debunking is NOT about taking one side of an argument, and then using whatever means possible to convince someone that you are correct. A good debunker is a good scientist. If there’s information that contradicts your position, then don’t ignore it, instead you should alter your position.

It’s not us vs. them. Invite everyone to point out errors in your facts, or in your reasoning. Focus especially on facts. Ideally you would be able to present enough verifiable facts that any reasonable person would come to the right conclusion.

There are various kinds of audiences you should have in mind when writing a skeptical article.

The easiest to write for is a community of like-minded skeptics. This is essentially preaching to the choir. It’s intellectually satisfying, but not terribly useful. These people are already immune to bunk, and at best this will be bolstering their immunity, maybe contributing somewhat to herd immunity. But really not a lot. The believers in bunk do not read Skeptic Magazine.

Then consider writing a generally accessible article for those people who have not formed a strong opinion, but are familiar with the subject matter. The “what’s up with that mystery missile story” people. This is also fairly easy, as you can generally just lay out the facts. Providing you can communicate reasonably, then things should work out fine. They are healthy people with enquiring minds. They may not have all the facts, but if given all the facts, they should be able to come to a reasonable conclusion.

Then there is writing for people who have no idea what the problem is in the first place. Like if you were asked to write a “chemtrail” article for USA Today, a popular American newspaper. Since the vast majority of people have not heard of chemtrails, you have to actually explain why people believe in them in the first place, and then explain what the problems with the theory are. This is analogous to inoculating them with a weak or dead form of the theory, and then letting their natural rationality take care of it, and hopefully build up some immunity to this and similar theories.

Then you descend to the various levels of bunk infection. There are a few levels worth noting here.

There’s the reasonable believer. They believe the theory, but they do so based on what they think are facts. They can be open to new facts, and can often be rescued. Be aware that they will have several infections of bunk, and you are not going to get rid of all of them. Don’t try to. Don’t even discuss the stronger bunk infections if possible. You can talk them out of chemtrails, and maybe the moon landing hoax, but 9/11 might be a bit too far. One step at a time.

Then there’s the “true believer”. The True Believer has lost all immunity to a particular subject. Anything you say that contradicts their belief must be a lie, because it contradicts a true belief. You need to establish common ground somehow, and work from there. Frequently they will not see reason, but they can be useful as a source of memetic material to help inoculate others. They will frequently run through the entire set of “evidence” one piece at a time, oblivious to the fact that everything they bring up is easily explained. This is useful simply for you to get familiar with the arguments used.

Then you have the extremists. People beyond the reach of reason, who don’t even have a good basis for their own beliefs. The lack of rationality in their arguments makes them both impossible to reason with, and basically useless for any part of debunking (except perhaps to illustrate how extreme the argument is - but that’s not a very good argument in itself, something of a fallacy). Best to ignore them, and hope they go away.

Some Guidelines for effective debunking communication

Tell the Truth

Don’t lie. Lies are evil. Lies will come back to hurt you. Lies are wrong. Don’t lie.

Don’t hide facts. If something conflicts with your theory, then change or expand the theory. If you hide a fact, it’s going to come up later. Be honest now, and you’ll be safe later.

Be polite.

Insulting people just polarizes them. Even perceived insults will have this effect. Telling someone they are “stupid”, “retarded”, or even that they “need to do more research”, is entirely unhelpful to progress. We are trying to get out the bunk, and if you insult people then they will just cling to their bunk tighter.

Of course there will be people who reject your ideas, no matter how you present them, polite or not. But always remember you have a greater audience than the person you are ostensibly discussing with. Part of that greater audience might be convinced, even if the individual is not.

Have a Thick Skin

People will insult you. They will call you stupid, evil, ignorant, a shill. They might even threaten you. Do not let this get to you, and do not let it tempt you to respond in kind. Being perceived as angry will only provide a distraction from what you are saying.

Don't be passive-aggressive

And don't be sarcastic. It's all stuff that can be perceived as insults, and all stuff that can distract. Instead be simple, honest, direct, and polite. Take a deep breath. If you feel venom as you are typing, it will probably come though in what you say. Be polite. Be nice. Do it honestly.

Don’t try to win

Don’t compromise truth for the sake of "winning". It’s not a contest. You don’t win if you convince someone of your point of view, but lie to them or withhold evidence along the way. You don’t win by bullying them with facts until they run away. You want a mutual agreement, something where both of you have arrived at a commonly held understanding of the facts that is closer to the truth. This might even mean you yourself may change your opinions a little. But that’s why they are just opinions.

Don’t be an expert

It does not matter what your credentials are. Don’t assume that makes you right. Being an expert gives you easier access to information, and it provides mental tools to help process that information. But you can’t just then say “because I say so”. You still have to explain, to demonstrate, and to provide the means of verifying your point of view.

Keep on target

One thing at a time. It’s very important to not lose focus, as there are lots of topic out there that will suck the life out of any discussion. One can be having a perfectly reasonable discussion about why contrail cirrus can last for several hours, and then someone says “yeah, I suppose you believe that WTC7 fell down because of a little fire”, and all of a sudden it’s tangent city. Of course you could fully debunk any WTC7 myth they throw at you but don’t go there. It’s just a huge time sink. Don’t allow off-topic discussion if possible, and just ignore it if you can’t.

Know Your Limits

Don’t dive into a highly hostile forum that has deep and bunk-filled views of the world. If they all agree, then you are going to get nowhere. There has to be at least some discussion going on there already, or some air of reason, for you to do anything productive. There’s a range of conspiracy forums. They all contain the full spectrum of conspiracy theorists, but some forums tend more towards the extremes than others . Read before writing there. Above Top Secret is more sensible than Prison Planet. Prison Planet is more sensible than David Icke. David Icke is more sensible than some of the more specialized forums out there.

Debunker or Skeptic?

Both, of course. But beware of language. For some “skeptics” are evil minionions, for other it’s “debunkers”. They have somehow got the wrong definition of the word. I hesitated somewhat in using “bunk” at all in this blog. But then it’s for people who understand what true scientific skepticism is, and what true debunking is. But you might want to be careful in an initial encounter not to alienate people by saying you are a “debunker”, if you know they are going to take that the wrong way. If you do describe yourself as a debunker (which I prefer), then make sure you can take the time to explain what it means. Debunking is just removing bunk - what do they want, you to leave the bunk alone?

Citation Needed

Back up your assertions. Provide the source of your data. Don’t just say “Aluminum makes up 8% of the Earth’s Crust”, unless you can back it up. If you are writing an article, then cite as many authoritative sources as possible. If it’s a comment, or in a discussion, don’t claim something unless you can quickly provide evidence of it.

Keep it simple

It’s not simple. It’s complicated. It’s very easy to make the explanation complicated, and then you either lose them by using science beyond their ken, or you get bogged down in minutiae. Keep it simple. “It can’t be true because … [of this one thing]”. Use the simplest thing that you think they will understand.

Quick example there - The Bard of Ely believed in chemtrails, and fought against all arguments. The breakthrough came when he realized that the solar halos could only be made by ice crystals, not powder. Unfortunately there’s no way of knowing that that was the one thing that would tip the balance.

Let them debunk it for you

Teach a man to fish and you won’t need to keep giving him fish. While it’s very temping to simply lay out the facts and prove that something is bunk, it’s much more productive for everyone to allow them to fill in a few steps for themselves. You need to gauge this carefully. Many people “want to believe”, so will resist doing anything that might harm their beliefs. But if you can get someone to look something up, perform a simple experiment, or fill in a logical step in an argument, then you win them over in a far more solid manner than if you did all the work for them.

You can extend this by actually teaching them how to debunk - or at least giving them little skills, like how to effectively use Google, or perhaps some little bit of math, or a reference they can use.

Know the Language

Believers often have a very specific usage or misunderstanding of specific terms. They frequently take any mention of some term (e.g. “aerosol”) to be related to their specific theory. Understand this when discussing the subject with them, and attempt to either explain what the term means, or use more neutral terms (dust, water vapor). Sometimes they will pick on an unusual phrase and simply misinterpret it, like “radiative forcing”. Here you’ve got to explain the term to them. You’ll have to do it again and again. You might want to consider putting up a little glossary of frequently misunderstood terms for your domain.

Don’t trust their eyes

Quite often you get statements like “I know what I saw”. When what they saw was something fairly boring, but it looks like something, and then they fit that into their world view. These types of things can be neatly described by:

A) Looks like: (something suspicious)

B) Hence: (How that fits into their world view)

C) But: (What it actually is)

A good example being the “Fema Coffins”:

A) Looks like: thousands of over-sized coffins stored in a field

B) Hence: FEMA must be planning to kill thousands of people

C) But: It’s actually just coffin liners

The cognitive dissonance occurs because for the believer it’s a lot simpler to go with A and B than to incorporate some new information C. They already “know” that there’s this huge population reduction conspiracy going on, so A and B fit that perfectly. C is new information that works against the conspiracy, so must be false.

Keep it Understandable

The most irrefutable debunk in the world is useless if nobody reads it. It needs to be written in an accessible manner. Give the simplest and easiest to check facts first. Make it entertaining. Politeness is a factor here again, as you can turn people off. Be polite, and more people will read it.

Use simple language. Use short sentences. Encapsulate single concepts in single paragraphs. Don’t include confusing things unless needed. Leave those to a sidebar/appendix/footnote. Keep it along the lines of “Because A, then B”.

Learn from History

Where did this conspiracy come from? What is the context? The fluoride conspiracy makes more sense in the context of the communist fear period of McCarthy in the 1950s. So what are the Zeitgeistical roots of this conspiracy? Chemtrails come from health scares on talk radio. UFO’s come from the Roswell incident and the Red Menace. The Federal Reserve conspiracies perhaps from anti-semitism.

Avoid repeating yourself

Think twice, write once. Make your explanations well worded, and in a form that can be re-used. It’s better to put some effort into writing a blog post, because then whenever someone raises the same point again, you can just point them at the post (I really should write a post explaining Radiative Forcing). If new information comes along, you can just update the post.

Avoid Repeating Others

Unless you are debunking a niche theory, then it’s likely that other people will have addressed any given point before, and often very well. If there’s a better explanation, then just link to it. If there are multiple explanations, then link to them. If you find you have to write additional material, then you might need to synthesize the various other articles into something new. But make sure that you are adding something. Make a copy of whatever you link to, in case it vanishes.

Don’t debunk where there is no evidence

A very common problem in bunk circles is when they raise the issue “you can’t prove that it isn’t”. Do not rise to this bait. The key point is that they have no evidence that it is. There are an infinite number of things that you can’t prove are not so (see: Russels Teapot), so for them to require you to debunk something, they first have to provide evidence that it IS so. Then your first step it to nullify that evidence by explaining it with conventional theories (long lasting trails in the sky = contrails). One their evidence is nullified, you don’t need to provided extra evidence against their theory, as they now still have no evidence for it. You are a debunker. The bunk here is the evidence and the reasoning they use. Remove that bunk and all you have is a random theory.

Last edited by a moderator: